Adapted from various sources, including Butler's Lives.

St. Maximus, Monk († 662; Feast – August 13)

Amidst the scandals, heresies, and schisms by which the devil has often renewed his assaults against the Church, Providence has always raised up defenders of the Faith, who,

by their fortitude and the holiness of their lives, stopped the fury of the flood, and repaired the ravages made on the Kingdom of Jesus Christ by base apostate arts. Thus, while Monothelism

triumphed on the Imperial throne, and in the principal sees of the East, this heresy found a formidable adversary in the person of the holy Pope, St. Martin I,

powerfully seconded by the whole Latin Church, and by a considerable part of the Greek Church; and while artifice, joined to persecution, labored in the East to annihilate the Truth,

faith alone shone with the highest glory and luster in the zeal, sufferings, and death of St. Maximus. Surnamed by the Greeks Homologetes or Confessor, Maximus was born at Constantinople in 580.

He sprung from one of the most noble and ancient families of that city, and was educated in a manner becoming his high birth, under the most able masters. But God inspired him with a knowledge

infinitely preferable to that which schools teach, and which the worldly-wise are often unacquainted with. God taught him to know himself, and conceive a due esteem for fervor and humility.

In vain, however, did his modesty seek to veil his merit – it was soon discovered at court; and the Emperor Heraclius set so high a value on his abilities, that he appointed Maximus his first secretary of state.

This busy scene, far from weakening the fondness he had ever entertained for solitude, filled him with apprehension, and determined him to withdraw from the corruption and poison of vain and worldly honors.

Amidst the scandals, heresies, and schisms by which the devil has often renewed his assaults against the Church, Providence has always raised up defenders of the Faith, who,

by their fortitude and the holiness of their lives, stopped the fury of the flood, and repaired the ravages made on the Kingdom of Jesus Christ by base apostate arts. Thus, while Monothelism

triumphed on the Imperial throne, and in the principal sees of the East, this heresy found a formidable adversary in the person of the holy Pope, St. Martin I,

powerfully seconded by the whole Latin Church, and by a considerable part of the Greek Church; and while artifice, joined to persecution, labored in the East to annihilate the Truth,

faith alone shone with the highest glory and luster in the zeal, sufferings, and death of St. Maximus. Surnamed by the Greeks Homologetes or Confessor, Maximus was born at Constantinople in 580.

He sprung from one of the most noble and ancient families of that city, and was educated in a manner becoming his high birth, under the most able masters. But God inspired him with a knowledge

infinitely preferable to that which schools teach, and which the worldly-wise are often unacquainted with. God taught him to know himself, and conceive a due esteem for fervor and humility.

In vain, however, did his modesty seek to veil his merit – it was soon discovered at court; and the Emperor Heraclius set so high a value on his abilities, that he appointed Maximus his first secretary of state.

This busy scene, far from weakening the fondness he had ever entertained for solitude, filled him with apprehension, and determined him to withdraw from the corruption and poison of vain and worldly honors.

About this time Monothelism gained admission at the Imperial court. Those that chiefly promoted it were Theodorus, Bishop of Pharan in Arabia, Sergius, Patriarch of Constantinople, and Cyrus,

Bishop of Phasis in Colchia, who was afterwards raised to the Patriarchal See of Alexandria. These prelates secretly favored the heresy of Eutyches. In feigned obedience to the laws of the Church and the state,

they received the Council of Chalcedon and admitted two natures, Divine and human, in Jesus Christ; but they denied that He had two distinct wills. They asserted that He had only one will –

compounded of the human and Divine – and they called it Theandric. Sergius later imposed upon Pope Honorius by a letter full of artifice, dissimulation, and falsehood.

He pretended that his only aim was to prevent disturbance and scandal. Honorius, thus imposed upon, returned an answer in 633, wherein he authorized silence on the question,

not to scandalize many churches, and lest ignorant persons, shocked at the expression of two operations, might look upon us as Nestorians; or as Eutychians, if we admitted but one operation in Christ.

Eventually, after the death of Pope Honorius, Pope John IV was elected in 640 and held a council at Rome, where the heresy of the Monothelites was condemned. Pope John wrote an apology for Honorius,

where he showed that this Pope had always held, with St. Leo and the whole Catholic Church, the doctrine of two wills in Jesus Christ; that he denied only that there was in Christ two wills contrary

and opposite to one another – that of the flesh and that of the spirit – as there is in us.

But prior to the condemnation, the heresy made progress under the countenance of the Emperor. Heraclius, who in his adversity had sought God with all his heart,

and had experienced the effects of His protection, in prosperity forgot his Divine Benefactor. He blushed not to favor heresy and to put his confidence in men expert in nothing save the vile arts of

dissimulation and deceit. He scandalized the whole Empire by his indolence, and tarnished by shameful disorders the glory he at first had acquired by his bravery and virtue.

He allowed the sect of Mohammed to establish itself among the Saracens, who during his reign, laid the foundations of their formidable empire. A succession of misfortunes at length wakened him from his lethargy;

and while each day acquainted him with some new defeat, he was penetrated with grief to see the Roman Empire, which had given laws to the universe, become the prey of barbarians.

His former bravery seemed to revive; he raised armies, but they were constantly overthrown. Astonished at the victories of the Arabs, who were greatly inferior to the Greeks in number, strength and discipline,

he demanded one day in council what could be the cause. All holding silence, a grave person of the assembly stood up and said,

But prior to the condemnation, the heresy made progress under the countenance of the Emperor. Heraclius, who in his adversity had sought God with all his heart,

and had experienced the effects of His protection, in prosperity forgot his Divine Benefactor. He blushed not to favor heresy and to put his confidence in men expert in nothing save the vile arts of

dissimulation and deceit. He scandalized the whole Empire by his indolence, and tarnished by shameful disorders the glory he at first had acquired by his bravery and virtue.

He allowed the sect of Mohammed to establish itself among the Saracens, who during his reign, laid the foundations of their formidable empire. A succession of misfortunes at length wakened him from his lethargy;

and while each day acquainted him with some new defeat, he was penetrated with grief to see the Roman Empire, which had given laws to the universe, become the prey of barbarians.

His former bravery seemed to revive; he raised armies, but they were constantly overthrown. Astonished at the victories of the Arabs, who were greatly inferior to the Greeks in number, strength and discipline,

he demanded one day in council what could be the cause. All holding silence, a grave person of the assembly stood up and said, It is because the Greeks have dishonored the sanctity of their profession,

and no longer retain the doctrine of Jesus Christ and His disciples. They insult and oppress one another, live in enmity and dissensions, and abandoned to the most infamous usuries and lusts.

The Emperor acknowledged the truth of this censure. In reality the vices of the Greeks at that period excited, according to one of their most celebrated writers, such odium,

that the very infidels held them in detestation.

St. Maximus declared himself on every occasion the defender of the Faith and of virtue; but neither his example or advice was followed. Seeing that his employment at court was incompatible

with his principles, and that he strove in vain to arrest the impetuosity of the torrent, he extorted from the Emperor permission to retire to Chrysopolis, where he took the monastic habit.

In his solitude he recommended to God the calamities of his people, and armed himself with fortitude against the dangers to which his soul was exposed. Dreading even in his monastery the snares which the

heretics laid on every side, he resolved to go to Africa, in search of a more secure retreat.

Sergius, the Monothelite Patriarch of Constantinople, dying about the year 638, was succeeded by Pyrrhus, a monk of Chrysopolis, who walked in the heretical footsteps of his predecessor.

Before his death Sergius had drawn up a decree favoring the Monothelites, which he convinced Emperor Heraclius to promulgate – which was done the year following.

As mentioned above the heresy was condemned under Pope John IV in 640, whereupon Heraclius retracted his decree and renounced his error before his death in 641.

He was succeeded by his eldest son, Constantine – but he died a few months later. His step-mother Martina and the new Patriarch Pyrrhus were accused of having poisoned him.

At least it is certain that Pyrrhus, in concert with that princess, placed her son Heraclonas on the imperial throne, rather than Constans – the son of Constantine, and grandson of Heraclius.

But they were not able to maintain this unjust usurpation. Before the end of October of the same year, Constans II was put in possession of the empire by the people;

Martina had her tongue torn out and Heraclonas his nose slit, and both were sent into exile by a decree of the senate.

Pyrrhus, having just reasons to fear the fury of the populace, secretly fled into Africa, where he endeavored to gain friends and converts to Monothelism. St. Maximus finding the Catholic Faith

thus dangerously exposed, exerted his most strenuous endeavors to preserve its integrity. The patrician Gregory, Governor of Africa, engaged St. Maximus to hold a public conference with Pyrrhus,

in hopes of his conversion. It was accordingly held at Carthage in July, 645. Along with the Governor, there was a numerous assembly of bishops and persons of distinction.

Pyrrhus arguing that as there was but one person in Jesus Christ which wills, concluded thence that there could be in Him no more than one will. St. Maximus proved against him that the unity of person

in Jesus Christ did not imply a unity of natures; that, being God and man at the same time, the divine and human natures must have their respective powers of volition; that it is an impiety to assert

that the will by which He created and governs all things is the same as that by which He ate and drank on earth, and prayed His Father to remove from Him, if possible, the chalice of His Passion;

that the will is a property essential to and inseparable from human nature, so that in denying Jesus Christ a human will, you strip Him of an essential part of His humanity – consequentially,

pure Eutychianism must be admitted, which consists of denying that there are two distinct natures in Jesus Christ.

The result of this conference was that Pyrrhus declared he had no more difficulties about any article, and showed a great desire to present in writing his retraction to the Pope.

He kept his word; and, traveling to Rome, he put into Pope Theodore's hands, in the presence of the clergy and people, a paper wherein he condemned all he had done or taught against the Faith.

But Pyrrhus soon renounced the orthodox sentiments he had published. On his coming to Ravenna, he relapsed into his errors at the instigation of the exarch, who flattered him with the hope of

recovering the see of Constantinople – currently occupied by another Monothelite, Paul. The latter persuaded the Emperor Constans to publish a new edict, favoring neither side,

but imposing silence on the matter. This edict appeared in 648, under the name of the Typus, or Fomulary.

The result of this conference was that Pyrrhus declared he had no more difficulties about any article, and showed a great desire to present in writing his retraction to the Pope.

He kept his word; and, traveling to Rome, he put into Pope Theodore's hands, in the presence of the clergy and people, a paper wherein he condemned all he had done or taught against the Faith.

But Pyrrhus soon renounced the orthodox sentiments he had published. On his coming to Ravenna, he relapsed into his errors at the instigation of the exarch, who flattered him with the hope of

recovering the see of Constantinople – currently occupied by another Monothelite, Paul. The latter persuaded the Emperor Constans to publish a new edict, favoring neither side,

but imposing silence on the matter. This edict appeared in 648, under the name of the Typus, or Fomulary.

Pope Theodore, informed of the apostasy of Pyrrhus, held a council in the Church of St. Peter, and pronounced against him a sentence of excommunication and deposition;

as also against Paul, whom he had in vain endeavored to reconcile to the Church by his letters and legates – who had been sent into exile by Paul. He also condemned the Typus of Constans.

But before the conclusion of this business, he was taken off by death on the 20th of April, 649. He was succeeded by Pope St. Martin I.

St. Maximus paid this Pope a visit at Rome, and assisted at a council held in the Lateran Basilica in 649. The heretic Paul died in 655 and Pyrrhus was illegally reinstalled in the

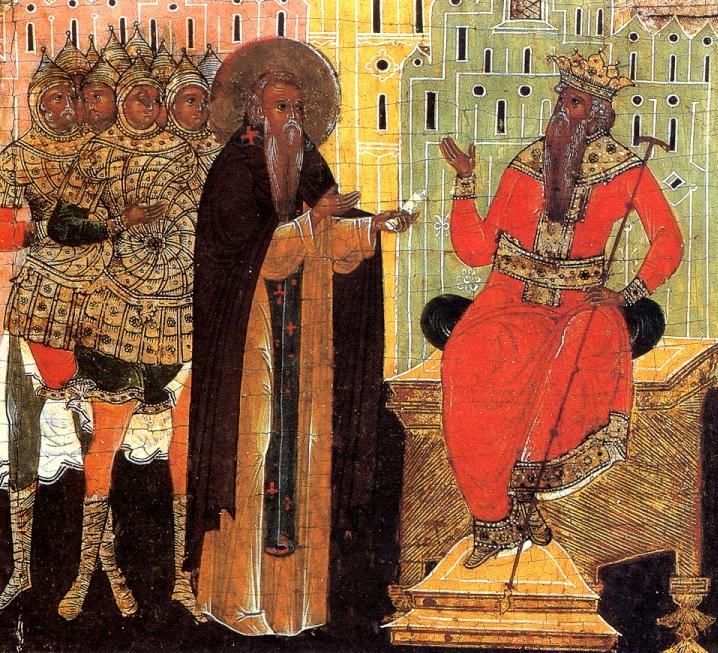

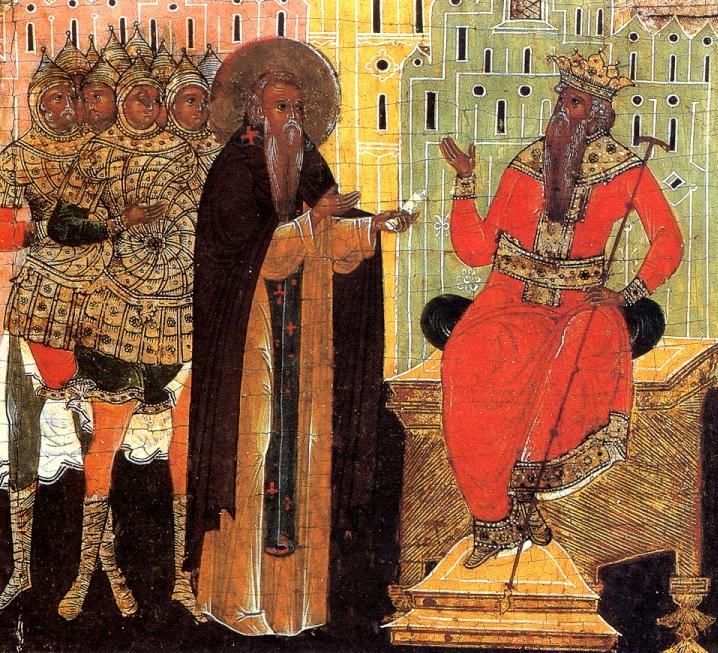

see of Constantinople. But he, too, died less than five months later, and was succeeded by yet another Monothelite named Peter. Pope St. Martin I, having been cruelly persecuted and exiled by the Emperor,

died from this abuse, also in 655 (image right). St. Maximus was soon after arrested at Rome, by the Emperor's order, and brought to Constantinople, along with Anastasius, his disciple, and another Anastasius,

who had been chancellor of the Roman church.

It was not hard for St. Maximus to justify himself. But at the same time he owned that, being at Rome, he had said to an officer that the Emperor’s power was not sacerdotal;

that the union proposed by the Typus could not be received; that the silence prescribed was a real suppression of the Faith, which could never be permitted; that, with such principles,

Jews and Christians might be united – the latter, silent on Baptism, the former on circumcision; that this union would find room for the Arians also, by the suppression of the

consubstantiality of the Word. The treasurer, not knowing what answer to make to this discourse, said only that a man such as Maximus ought not to be tolerated in the Empire.

Others added reproaches still more injurious.

Anastasius, the Saint's disciple, was afterwards examined, but as he could not raise his voice enough to be heard by all, the guards beat him so cruelly, that they left him half dead.

The two confessors were then brought back to their prison.

The same evening, the patrician Troilus, accompanied by two officers of the palace, came to see St. Maximus, with a design to persuade him to communicate with the church of Constantinople.

The Saint desired that they would first condemn the heresy of the Monothelites, who had been excommunicated by the council in Rome, and reproached them with having changed their own doctrine.

As they accused him of condemning them all, he answered:

The same evening, the patrician Troilus, accompanied by two officers of the palace, came to see St. Maximus, with a design to persuade him to communicate with the church of Constantinople.

The Saint desired that they would first condemn the heresy of the Monothelites, who had been excommunicated by the council in Rome, and reproached them with having changed their own doctrine.

As they accused him of condemning them all, he answered: God forbid I should condemn anyone; but I would rather die than err against the Faith in the smallest article.

The officers pressed him to receive the Typus for the sake of peace, and confessed at the same time that they acknowledged two wills in Christ. The Saint then prostrated himself on the earth,

and with tears in his eyes said: It is not my intention to displease the Emperor, but I cannot consent to offend God.

He declared that it was not his intention to charge the Emperor with heresy,

since the Typus was not his work, which he did not sign until imposed upon by the enemies of the church; but he added that he ardently wished him to disavow it,

as his grandfather Heraclius had disavowed the Ecthesis – a similar document imposing silence.

St. Maximus and his disciples underwent a second interrogatory in the palace council chamber, before the senate, at which were present Peter, Patriarch of Constantinople, and Macarius,

Patriarch of Antioch – both Monothelites. Here they again declared that they would adhere inviolably to the Faith of their fathers, and to the definition of the council previously mentioned.

After several debates, they were sent back to prison. On the Feast of Pentecost, a messenger from the Patriarch Peter endeavored to prevail upon St. Maximus to submit.

As he was threatened with excommunication and a cruel death, he answered that all he desired was that the will of God be done in his regard.

The day after this conference, the three were banished into Thrace and imprisoned in three different places, without provision for their subsistence and with no other covering than a few rags.

A little time after, commissaries arrived to examine the Saint anew in his place of exile. They were sent by the Emperor and the Patriarch, and among them was a bishop named Theodosius.

St. Maximus proved before them that there must necessarily be two wills in Jesus Christ, and that it is never lawful to suppress the doctrine of Faith. His arguments were so convincing that

Theodosius agreed the Typus had a dangerous tendency; and the commissaries even went so far as to sign an act of reconciliation with St. Maximus. Theodosius, moreover, promised to go to Rome,

and make his peace with the Church. Then all rose up weeping with joy; and, after praying some time on their knees, they kissed the Book of the Gospels, the Cross, an Icon of Jesus Christ and the Blessed Virgin,

and laid their hands upon them in confirmation of their agreement. Theodosius, at taking leave, made the Saint a present of some money and clothes.

Nonetheless, this reconciliation came to nothing. In 656 the Emperor sent the consul Paul with orders to bring St. Maximus back to the monastery of St. Theodore de Rege, near Constantinople.

There was no regard paid to the age or rank which the Saint once held at court; he was treated on the road with the utmost barbarity, arriving at Rege on September 13. The patricians Epiphanius and Troilus,

as well as Bishop Theodosius, went to visit him there, attended with a numerous train. They insisted much on the promise he supposedly had made of submitting to the Emperor's request.

Maximus answered that he was ready to obey the prince in all things that regarded temporal affairs. Upon this, loud clamors were raised against him, and after some debate, Epiphanius addressed him:

Hear the envoy of the Emperor. All the West and all those who have been seduced in the East have their eyes fixed on you. Are you willing to communicate with us, and receive the Typus?

We come in person to salute you; we present you our hand, we will wait on you to the cathedral, and along with you there receive the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ,

in that solemn manner acknowledging you as our father. We are persuaded that all those who have separated from our communion will no sooner see you communicating with the church of Constantinople

than they will follow your example.

My lord,

said St. Maximus, directing his discourse to Bishop Theodosius, we must all appear before the judgment seat of God. You know the solemn agreement that has been made between us,

ratified on the Gospels, the Cross, on the Icon of Jesus Christ and of His Holy Mother.

What would you have me do?

answered Theodosius, bowing his head, and in the tone of a flatterer willing to pay

his court, seeing the Emperor is of another opinion?

Why then,

replied Maximus, did you put your hand on the Gospels? For my part, I declare that nothing shall induce me to comply with your

demand. What reproaches would I not suffer from my conscience, what answer could I make to God, if I renounced the Faith for human respect?

At these words they all rose up in transports of rage. They fell upon the Saint, they buffeted him, they tore his beard, they covered him with spittle and filth from head to foot,

so that it was necessary to wash his clothes to remove the infectious stench, which hindered a near approach to him. It is wrong,

said Theodosius, to treat him in this unworthy manner;

it would be enough to report his answer to the Emperor.

They then halted their barbarous treatment, and confined themselves to abusive insolent language. Then Troilus said to the holy monk,

We only ask you to sign the Typus; believe what you will in your heart.

It is not to the heart alone,

replied Maximus, that God has confined our duty;

we are also obliged to confess Jesus Christ before men.

With my advice,

said Epiphanius, you would be tied to a stake in the midst of the city, to be bruised and spit upon by the populace.

If the barbarians left us time to breathe,

said some others, we would treat you as you deserve, the Pope himself, and all your followers.

They all then withdrew, saying:

This man is possessed by the devil; but let us dine before we make a report of his insolence and obstinacy to the Emperor.

The morning after, St. Maximus was sent under a guard of soldiers to Selymbria, and from thence brought to the camp. As it was reported that he had denied the Blessed Virgin Mary

to be the Mother of God, he pronounced anathema against the supporters of such a heresy. He gave instructions in the camp, which were heard with much respect; and all besought God to grant him

the necessary courage to finish happily his course. Seeing how much he was honored, his guard removed him two miles distant, where they allowed him some rest; then they obliged him to mount his

horse and conducted him to prison.

Some time after, St. Maximus and the two Anastasiuses were brought back again to Constantinople. They were made to appear before a synod of Monothelites, who anathematized them,

together with Pope St. Martin I, St. Sophronius of Jerusalem, and all who adhered to them. The sentence pronounced against them ran thus: Having been canonically condemned,

you would justly undergo the severity of the law for your impieties. But although there be no punishments proportioned to your crimes, we choose not to treat you according to the rigor of the law;

we touch not your life, abandoning you to the justice of the Sovereign Judge. We order the prefect here present, to conduct you to the prætorium, where after having been scourged, your tongue –

the instrument of your blasphemies – shall be torn out, and your right hand – with which you have written these blasphemies – shall be cut off. We will that you be afterwards exposed

in the twelve wards of the city; then that you be banished and imprisoned for the remainder of your days to expiate your sins by your tears.

The three having suffered at Constantinople the punishments named in the sentence, were then sent into banishment, arriving at Sarmatia (Eastern Ukraine / Western Russia) in June of 662.

They were then separated from each other. The torments he had endured joined to the fatigue of the journey so weakened the monk Anastasius, that he died on July 24 of the same year.

The other Anastasius did not long survive him. St. Maximus had to be conducted in a litter to the place of his imprisonment. He foretold the day of his death which happened later that same year,

or early in the following, he being about 80 years old. The Greeks celebrate two feasts in his honor: on January 21 and August 13. The Roman Martyrology gives the latter as the day of his death;

but others believe that to be the day of the translation of his relics. He and his companions are ranked as Confessors, though they could easily be considered Martyrs. (Images above left –

St. Maximus remained firm even after his tongue and right hand had been cut off; Reliquary of the hand of St. Maximus. Image above right – Tomb of St. Maximus

Back to "In this Issue"

Back to Top

Back to Saints

Alphabetical Index; Calendar List of Saints

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com

Amidst the scandals, heresies, and schisms by which the devil has often renewed his assaults against the Church, Providence has always raised up defenders of the Faith, who,

by their fortitude and the holiness of their lives, stopped the fury of the flood, and repaired the ravages made on the Kingdom of Jesus Christ by base apostate arts. Thus, while Monothelism

triumphed on the Imperial throne, and in the principal sees of the East, this heresy found a formidable adversary in the person of the holy Pope, St. Martin I,

powerfully seconded by the whole Latin Church, and by a considerable part of the Greek Church; and while artifice, joined to persecution, labored in the East to annihilate the Truth,

faith alone shone with the highest glory and luster in the zeal, sufferings, and death of St. Maximus. Surnamed by the Greeks Homologetes or Confessor, Maximus was born at Constantinople in 580.

He sprung from one of the most noble and ancient families of that city, and was educated in a manner becoming his high birth, under the most able masters. But God inspired him with a knowledge

infinitely preferable to that which schools teach, and which the worldly-wise are often unacquainted with. God taught him to know himself, and conceive a due esteem for fervor and humility.

In vain, however, did his modesty seek to veil his merit – it was soon discovered at court; and the Emperor Heraclius set so high a value on his abilities, that he appointed Maximus his first secretary of state.

This busy scene, far from weakening the fondness he had ever entertained for solitude, filled him with apprehension, and determined him to withdraw from the corruption and poison of vain and worldly honors.

Amidst the scandals, heresies, and schisms by which the devil has often renewed his assaults against the Church, Providence has always raised up defenders of the Faith, who,

by their fortitude and the holiness of their lives, stopped the fury of the flood, and repaired the ravages made on the Kingdom of Jesus Christ by base apostate arts. Thus, while Monothelism

triumphed on the Imperial throne, and in the principal sees of the East, this heresy found a formidable adversary in the person of the holy Pope, St. Martin I,

powerfully seconded by the whole Latin Church, and by a considerable part of the Greek Church; and while artifice, joined to persecution, labored in the East to annihilate the Truth,

faith alone shone with the highest glory and luster in the zeal, sufferings, and death of St. Maximus. Surnamed by the Greeks Homologetes or Confessor, Maximus was born at Constantinople in 580.

He sprung from one of the most noble and ancient families of that city, and was educated in a manner becoming his high birth, under the most able masters. But God inspired him with a knowledge

infinitely preferable to that which schools teach, and which the worldly-wise are often unacquainted with. God taught him to know himself, and conceive a due esteem for fervor and humility.

In vain, however, did his modesty seek to veil his merit – it was soon discovered at court; and the Emperor Heraclius set so high a value on his abilities, that he appointed Maximus his first secretary of state.

This busy scene, far from weakening the fondness he had ever entertained for solitude, filled him with apprehension, and determined him to withdraw from the corruption and poison of vain and worldly honors. But prior to the condemnation, the heresy made progress under the countenance of the Emperor. Heraclius, who in his adversity had sought God with all his heart,

and had experienced the effects of His protection, in prosperity forgot his Divine Benefactor. He blushed not to favor heresy and to put his confidence in men expert in nothing save the vile arts of

dissimulation and deceit. He scandalized the whole Empire by his indolence, and tarnished by shameful disorders the glory he at first had acquired by his bravery and virtue.

He allowed the sect of Mohammed to establish itself among the Saracens, who during his reign, laid the foundations of their formidable empire. A succession of misfortunes at length wakened him from his lethargy;

and while each day acquainted him with some new defeat, he was penetrated with grief to see the Roman Empire, which had given laws to the universe, become the prey of barbarians.

His former bravery seemed to revive; he raised armies, but they were constantly overthrown. Astonished at the victories of the Arabs, who were greatly inferior to the Greeks in number, strength and discipline,

he demanded one day in council what could be the cause. All holding silence, a grave person of the assembly stood up and said,

But prior to the condemnation, the heresy made progress under the countenance of the Emperor. Heraclius, who in his adversity had sought God with all his heart,

and had experienced the effects of His protection, in prosperity forgot his Divine Benefactor. He blushed not to favor heresy and to put his confidence in men expert in nothing save the vile arts of

dissimulation and deceit. He scandalized the whole Empire by his indolence, and tarnished by shameful disorders the glory he at first had acquired by his bravery and virtue.

He allowed the sect of Mohammed to establish itself among the Saracens, who during his reign, laid the foundations of their formidable empire. A succession of misfortunes at length wakened him from his lethargy;

and while each day acquainted him with some new defeat, he was penetrated with grief to see the Roman Empire, which had given laws to the universe, become the prey of barbarians.

His former bravery seemed to revive; he raised armies, but they were constantly overthrown. Astonished at the victories of the Arabs, who were greatly inferior to the Greeks in number, strength and discipline,

he demanded one day in council what could be the cause. All holding silence, a grave person of the assembly stood up and said,  The result of this conference was that Pyrrhus declared he had no more difficulties about any article, and showed a great desire to present in writing his retraction to the Pope.

He kept his word; and, traveling to Rome, he put into Pope Theodore's hands, in the presence of the clergy and people, a paper wherein he condemned all he had done or taught against the Faith.

But Pyrrhus soon renounced the orthodox sentiments he had published. On his coming to Ravenna, he relapsed into his errors at the instigation of the exarch, who flattered him with the hope of

recovering the see of Constantinople – currently occupied by another Monothelite, Paul. The latter persuaded the Emperor Constans to publish a new edict, favoring neither side,

but imposing silence on the matter. This edict appeared in 648, under the name of the Typus, or Fomulary.

The result of this conference was that Pyrrhus declared he had no more difficulties about any article, and showed a great desire to present in writing his retraction to the Pope.

He kept his word; and, traveling to Rome, he put into Pope Theodore's hands, in the presence of the clergy and people, a paper wherein he condemned all he had done or taught against the Faith.

But Pyrrhus soon renounced the orthodox sentiments he had published. On his coming to Ravenna, he relapsed into his errors at the instigation of the exarch, who flattered him with the hope of

recovering the see of Constantinople – currently occupied by another Monothelite, Paul. The latter persuaded the Emperor Constans to publish a new edict, favoring neither side,

but imposing silence on the matter. This edict appeared in 648, under the name of the Typus, or Fomulary. The same evening, the patrician Troilus, accompanied by two officers of the palace, came to see St. Maximus, with a design to persuade him to communicate with the church of Constantinople.

The Saint desired that they would first condemn the heresy of the Monothelites, who had been excommunicated by the council in Rome, and reproached them with having changed their own doctrine.

As they accused him of condemning them all, he answered:

The same evening, the patrician Troilus, accompanied by two officers of the palace, came to see St. Maximus, with a design to persuade him to communicate with the church of Constantinople.

The Saint desired that they would first condemn the heresy of the Monothelites, who had been excommunicated by the council in Rome, and reproached them with having changed their own doctrine.

As they accused him of condemning them all, he answered: