Adapted from Various Sources.

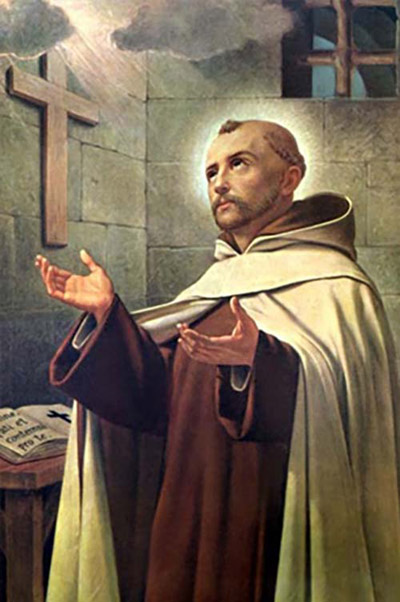

Let us go with the Church to Mount Carmel, and offer our grateful homage to St. John of the Cross, who, following in the footsteps of St. Teresa of Jesus (of Avila), opened a safe way to souls seeking God.

The growing disinclination of the people for mental prayer was threatening the irreparable destruction of piety, when in the sixteenth century the divine goodness raised up Saints whose teachings and holiness responded to the needs of the new times. Doctrine does not change: the asceticism and mysticism of that age transmitted to the succeeding centuries the echo of those that had gone before. But their explanations were given in a more instructive way and analyzed more clearly; their methods aimed at obviating the risk of illusion, to which souls were exposed by their isolated devotion. It is but just to recognize that under the ever-fruitful action of the Holy Ghost, the study of supernatural states became more extended and more precise.

The early Christians, praying with the Church, living daily and hourly the life of Her Liturgy, kept Her stamp upon them

in their personal relations with God. Thus it came about that, under the persevering and transforming influence of the Church,

and participating in the graces of light and union, and in all the blessings of that Church – the beloved so pleasing to the Spouse –

they assimilated Her sanctity to themselves, without any further trouble but to follow their Mother with docility and allow themselves

to be carried securely in Her arms. Thus they applied to themselves the words of the Lord: Unless you become as little children,

you shall not enter into the kingdom of Heaven.

We need not be surprised that there was not then the frequent and assiduous

assistance of a particular spiritual director for each soul. Special guides are not so necessary to the members of a caravan or

of an army; it is isolated travelers that stand in need of them; and even with these special guides, they can never have the same

security as those who follow the caravan or the army.

This was understood, in the course of the last few centuries, by the men of God who, taking their inspiration from the

many different aptitudes of souls, became the leaders of schools of spirituality – one, it is true, in aim, but differing in the methods

they adopted for counteracting the dangers of individualism. In this campaign of restoration and salvation, where the worst enemy of

all was illusion under a thousand forms, with its subtle roots and its endless wiles, St. John of the Cross was the living image of

the Word of God, more piercing than any two-edged sword, reaching unto the division of the soul and the spirit, of the joints also

and the marrow;

for he read, with unfailing glance, the very thoughts and intentions of hearts. Let us listen to his words.

Though he belongs to more modern times, he is evidently a son of the ancients:

The journey of the soul to the divine union is called night, for three reasons. The first is derived from the point

from which the soul sets out, the privation of the desire of all pleasure in all the things of this world, by an entire detachment

therefrom. The second, from the road by which it travels – that is, faith; for faith is obscure, like night, to the intellect.

The third, from the goal to which it tends – God, incomprehensible and infinite, Who in this life is as night to the soul. We must

pass through these three nights if we are to attain to the divine union with God.

(The Ascent of Mount Carmel, Book 1, ch. 2.)

O spiritual soul, when thou seest thy desire obscured, thy will arid and constrained, and thy faculties incapable

of any interior act, be not grieved at this, but look upon it rather as a great good, for God is delivering thee from thyself,

taking the matter out of thy hands; for however strenuously thou mayest exert thyself, thou wilt never do anything so faultlessly,

so perfectly, and securely as now – because of the impurity and torpor of thy faculties – when God takes thee by the hand, guides

thee safely in thy blindness, along a road and to an end thou knowest not, and whither thou couldst never travel guided by thine

own eyes, and supported by thy own feet.

(The Dark Night of the Soul, Book 2, ch. 16.)

The life of St. John of the Cross is thus related by holy Church:

St. John of the Cross was born of pious parents at Fontiveros in Spain. From his infancy it was evident how dear he would be to the Virgin Mother of God, for at five years of age, having fallen down a well, he was held up by Our Lady in Her arms, so that he sustained no injury. He had so great a desire of suffering, that when he was but nine years old, he discarded his soft bed and slept on bundles of sticks. As a young man, he devoted himself to the service of the sick in the hospital of Medina del Campo. Here he showed the ardor of his charity by undertaking the vilest offices; and his example incited others to devote themselves to the same charitable deeds. But as God called him still higher, he entered the Order of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel, where he was made priest in obedience to his superiors; and in his ardor for more severe discipline and a more austere manner of life, he obtained their leave to observe the primitive rule of the Order. Being ever mindful of Our Lord’s Passion, he declared war against himself as against his worst enemy; and by vigils, fasting, iron disciplines, and every kind of penance, he soon crucified his flesh with its vices and concupiscence; so that St. Teresa of Avila considered him worthy to be numbered among the holiest and purest souls then adorning God's Church.

Besides his singular austerity of life, St. John was equipped for the spiritual combat with the armor of all virtues. He devoted himself assiduously to the contemplation of divine things, in which he frequently experienced long and wonderful ecstasies; and his heart burned with such love of God that this divine fire could not be contained within, but would break forth and light up his countenance. He was exceedingly zealous for his neighbors' salvation, and devoted himself to preaching the Word of God and administering the Sacraments. Enriched with all these merits and kindled with the desire of promoting stricter discipline, he was given by God as a companion to St. Teresa, that as she had restored primitive observance among the sisters of the Order of Carmel, she might with St. John's help do the same among the brethren. In carrying out this divine work, he, together with that handmaid of God, underwent innumerable labors; and fearing neither sufferings nor dangers, he visited all the monasteries founded by the holy virgin in Spain, and himself founded others, propagating in all the restored observance and strengthening it by his words and example. He has thus every right to be called, after St. Teresa, the first professed and the father of the Discalced Carmelites.

He preserved his virginity intact, and not only repulsed impudent women, who tried to ensnare him, but even gained them to Christ.

The Holy See has declared that, like St. Teresa, he was divinely instructed in explaining the hidden mysteries of God; and he wrote

books on mystical theology full of divine wisdom. When asked one day by Christ what reward he desired for so many labors, he replied:

Lord, to suffer and be contemned for Thy sake! He was renowned for his power over the devils, whom he often cast out of the possessed;

and also for the gifts of discernment of spirits and prophecy; while such was his humility that he often begged Our Lord to let him die

in a place where no one knew him. His prayer was granted; and after a cruel malady and the patient endurance of five ulcers in his leg,

sent to him to satisfy his love of suffering, he fell asleep in the Lord at Ubeda, having received the Last Sacraments of the Church in

the holiest dispositions, and embracing the image of Christ crucified, Whom he had ever had in his heart and on his lips. His last words

were: Into Thy hands I commend my spirit. His death took place on the day and at the hour he had foretold, in the year of salvation 1591,

the forty-ninth of his age. A brilliant globe of fire received his departing soul; while his body gave forth a most sweet perfume,

and is still reverently preserved incorrupt at Segovia. As he was renowned for many miracles both before and after death,

Pope Benedict XIII enrolled him among the Saints.

He preserved his virginity intact, and not only repulsed impudent women, who tried to ensnare him, but even gained them to Christ.

The Holy See has declared that, like St. Teresa, he was divinely instructed in explaining the hidden mysteries of God; and he wrote

books on mystical theology full of divine wisdom. When asked one day by Christ what reward he desired for so many labors, he replied:

Lord, to suffer and be contemned for Thy sake! He was renowned for his power over the devils, whom he often cast out of the possessed;

and also for the gifts of discernment of spirits and prophecy; while such was his humility that he often begged Our Lord to let him die

in a place where no one knew him. His prayer was granted; and after a cruel malady and the patient endurance of five ulcers in his leg,

sent to him to satisfy his love of suffering, he fell asleep in the Lord at Ubeda, having received the Last Sacraments of the Church in

the holiest dispositions, and embracing the image of Christ crucified, Whom he had ever had in his heart and on his lips. His last words

were: Into Thy hands I commend my spirit. His death took place on the day and at the hour he had foretold, in the year of salvation 1591,

the forty-ninth of his age. A brilliant globe of fire received his departing soul; while his body gave forth a most sweet perfume,

and is still reverently preserved incorrupt at Segovia. As he was renowned for many miracles both before and after death,

Pope Benedict XIII enrolled him among the Saints.

We will add to these brief lessons from the Roman Breviary some facts from the Saint's life which underscore how well

he deserved the title, of the Cross

:

After the ordination of St. John to the priesthood in 1567, when he was 25 years old, he was inflamed with a desire for greater retirement, for which purpose he began to consider entering the Carthusian Order. St. Teresa of Avila was then busy in establishing her reform of the Carmelites, and coming to Medina del Campo, she heard of the extraordinary virtue of Friar John. She told him that God had called him to sanctify himself in the Order of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, that she had received authority from the Superior General to found two reformed houses of men, and that he himself should be the first instrument of so great a work. St. John acquiesced to her proposal and entered this new religious house in a perfect spirit of sacrifice. After about two months he was joined by some others, who all renewed their profession on Advent Sunday, 1568. This was the beginning of the Discalced Carmelite Friars, whose institute was approved by Pope St. Pius V and, in 1580, confirmed by Pope Gregory XIII. So great were the austerities of these primitive Carmelites, that St. Teresa saw it necessary to prescribe them a mitigation. The example and exhortations of St. John inspired his fellow religious with a perfect spirit of solitude, humility, and mortification. His wonderful love of the Cross appeared in all his actions, and it was by meditating continually on the sufferings of Christ that it increased daily in his soul: for love made him desire to resemble his Crucified Redeemer in all manner of humiliations and sufferings.

St. John, after tasting the first sweetness of holy contemplation, found himself deprived of all sensible devotion. This spiritual dryness was followed by interior trouble of mind, scruples, and a distaste for spiritual exercises, which he was yet careful never to forsake. The devils then assaulted him with violent temptations, while men persecuted him with virulent calumnies. But the most terrible of these pains was that of scrupulosity and interior desolation, in which he seemed to see Hell open, ready to swallow him up. He describes admirably what a soul feels in this trial in his book called The Dark Night of the Soul. This state of interior desolation, contemplative souls, in some degree, must pass through before their hearts are prepared to receive the communication of God's special graces.

In 1576 St. Teresa sent for St. John and appointed him the spiritual director of her convent in Avila, hoping to retrench

at least the frequent visits of secular persons. St. John soon enforced the shutting up of the parlors, where such visits occurred,

and cut off other scandalous abuses which were inconsistent with religious life. The old Carmelite friars looked upon this reformation,

though undertaken with the license and approbation of the Superior General, given to St. Teresa, as a rebellion against their Order.

In their general chapter held in Piacenza, Italy, they condemned St. John as a fugitive and an apostate. The following year,

his enemies broke open his door, and tumultuously carried him off to the prison of his convent. Knowing the veneration which

the people of Avila had for St. John, they removed him thence to the monastery of Toledo, where he was locked up in a stifling cell,

measuring barely six by ten feet, into which no light had admittance but through a little hole three fingers broad. Scarcely any other

nourishment was allowed him during the nine months which he remained there, but bread, water, and a little salted fish. He escaped in

1578 due to the purposeful

In 1576 St. Teresa sent for St. John and appointed him the spiritual director of her convent in Avila, hoping to retrench

at least the frequent visits of secular persons. St. John soon enforced the shutting up of the parlors, where such visits occurred,

and cut off other scandalous abuses which were inconsistent with religious life. The old Carmelite friars looked upon this reformation,

though undertaken with the license and approbation of the Superior General, given to St. Teresa, as a rebellion against their Order.

In their general chapter held in Piacenza, Italy, they condemned St. John as a fugitive and an apostate. The following year,

his enemies broke open his door, and tumultuously carried him off to the prison of his convent. Knowing the veneration which

the people of Avila had for St. John, they removed him thence to the monastery of Toledo, where he was locked up in a stifling cell,

measuring barely six by ten feet, into which no light had admittance but through a little hole three fingers broad. Scarcely any other

nourishment was allowed him during the nine months which he remained there, but bread, water, and a little salted fish. He escaped in

1578 due to the purposeful negligence

of his kindly jailer, and the protection of the Mother of God. In his destitute condition

he had been favored with many heavenly comforts, which made him afterwards say, Be not surprised that I show so great a love for

suffering; God gave me a high idea of their merit and value when I was in the prison of Toledo.

There were still many fervent religious in the Carmelite Order, and St. John was soon returned to several positions of authority. In all his employments the austerities which he practiced seemed to exceed all bounds. He only slept two or three hours a night, spending the rest of the night hours in prayer before the Blessed Sacrament. Three things he frequently asked of God: 1) that he might not pass one day without suffering something; 2) that he might not die a superior; 3) rather, that he might end his life in humiliations, disgrace and contempt.

God was pleased to answer his prayer by a second grievous persecution from his own brethren before his death. There were

in the Order two fathers of great authority, who declared themselves his implacable enemies, harboring malice and envy in their breasts,

which they cloaked under the sanctified name of holy zeal.

They were puffed up with an opinion of their own learning and with

the applause which they acquired by their talents in the pulpit, on which pretense they neglected all the duties of their Rule.

St. John, when Provincial of Andalusia, after frequent admonitions of this irregularity, which tended to the destruction of religious

discipline in their Order, finding no other remedy took effect, forbade them to preach, and confined them to their convents. Instead

of humble submission they were stung with bitter gall in their hearts, and regarded this treatment as an unjust and unreasonable

impediment to the exercise of their zeal, for which they thought themselves qualified; as if any other disposition than that of distrust

in themselves and perfect humility could draw down the blessing of God upon their functions. One of them, called Fray Diego Evangelista,

ran over the whole province to trump up accusations against the servant of God, and boasted that he had sufficient proofs to have him

expelled from the Order. The Saint said nothing all this while, except that he was ready to receive with joy any punishment.

Everybody at that time forsook him; all were afraid of having any dealing with him, and burned the letters which they had received

from him, lest they might be involved in his disgrace.

St. John, living in the practice of extreme austerities, and in continual contemplation, fell sick, and when he could no longer conceal his illness, the provincial ordered him to leave the place where he was, being destitute of all means of relief, and gave him the choice either to go to Baéza or Ubeda. The first was a very convenient convent, and had for Prior an intimate friend of the Saint. The other was poor, and Fray Francisco Crisóstomo was Prior there, the other person he had formerly corrected, and who was no less his enemy than Fray Diego. The love of suffering made St. John prefer this house of Ubeda. The fatigue of his journey had caused his leg to swell exceedingly, and it burst in many places from the heel to the knee, besides five ulcers under his foot. He suffered excessive pains from the violence of the inflammation, and from the frequent incisions and operations of the surgeons, from the top to the bottom of his leg. His fever all this time allowed him no rest. These racking pains he suffered three whole months with admirable patience, in continual peace, tranquility and joy, never making the least complaint, but often embracing the crucifix, and pressing it close upon his breast when the pain was very sharp.

The unworthy Prior treated him with the utmost inhumanity, forbade anyone to be admitted to see him, changed the infirmarian because he treated him with kindness, locked him up in a little cell, made him continual harsh reproaches, and would not allow anything but the hardest bread and food, refusing him even what lay persons sent in for him; all which the Saint suffered with joy in his countenance. God Himself was pleased to complete his sacrifice, and abandoned him sometime to a great spiritual dryness, and a state of interior desolation. But his love and patience were the more heroic. God likewise stretched out His hand to bring the dove into the ark when she seemed almost sinking in the waters, overwhelming his chaste soul again with the torrent of His delights with which He so often strengthened the martyrs, converting their torments into pleasures.

The Provincial happening to come to Ubeda a few days before the Saint's death, was grieved to see this barbarous usage, opened the door of his cell, and said that such an example of invincible patience and virtue ought to be public, not only to his religious brethren, but to the whole world. The Prior of Ubeda opened his eyes, begged the Saint's pardon, received his instructions for the government of his community, and afterwards accused and condemned himself with many tears.

As for the Saint himself, we cannot give a better description of the situation of his holy soul in his last moments than in his own words, where he speaks of the death of a saint:

Perfect love of God makes death welcome, and most sweet to a soul. They who love thus, die with burning ardors and

impetuous flights, through the vehemence of their desires of mounting up to their Beloved. The rivers of love in the heart now swell

almost beyond all bounds, being just going to enter the ocean of love. So vast and so serene are they that they seem even now calm seas,

and the soul overflows with torrents of joy, upon the point of entering into the full possession of God. She seems already to behold

that glory, and all things in her seem already turned into love, seeing there remains no other separation than a thin web, the prison

of the body being almost broken.

(The Living Flame of Love)

The spirit of Christianity is the spirit of the Cross. To attain to and live by pure love, we must live and die upon the Cross, or at least in the spirit of the Cross. Jesus merited all the graces we receive by suffering for us; and it is by suffering with Him that we are best prepared to be enriched with them. Hence afflictions are part of the portion, together with His consolations, He has promised to His most beloved servants.

NEW: Alphabetical Index

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com