In this series, condensed from a book written by Fr. Northcote prior to 1868 on various famous Sanctuaries of Our Lady, the author succeeds in defending the honor of Our Blessed Mother and the truth of the Catholic Faith against the wily criticism of many Protestants.

There are some other French sanctuaries of Our Lady concerning which we must claim an antiquity which will doubtless provoke a contemptuous smile from readers of a critical temper. The bare notion of images of the Blessed Virgin having been brought to France, and churches built in Her honor, by the immediate followers of the Apostles appears to many minds not merely legendary but apocryphal; yet in the history of the Church of Chartres we are presented with a greater wonder still – for that venerable city claims pre-eminence among all those which boast of their ancient devotion to Mary from the fact of its having been the seat of a religious worship, which we may say was directed to Her even before Her birth.

This statement, which at first sight appears preposterous, bears, nevertheless, more substantial appearance of probability than many of those other legends. Chartres, as we learn from Caesar, was the great seat of Druidical worship in Gaul. The Druid priests held their principal assemblies in its neighborhood, and their supreme chief always resided there. The Druids, as is well known, performed their religious ceremonies, not in temples, but in woods, and one of these sacred woods covered the little hill now occupied by the cathedral of Chartres. In this wood was a cave or grotto, where, according to ancient tradition, an altar was erected to the Virgo paritura – the Virgin who was to bring forth (or give birth) – to whom moreover the king and his people solemnly consecrated themselves. This tradition loses all character of improbability when we remember that the mystery to which it alludes was to be found in the religious belief of most pagan nations of antiquity. It formed, in fact, a portion of that primitive tradition which, however much corrupted and overlaid by fables, had never been entirely effaced. Traces of it are to be found in the mythologies of the Latins, the Chaldeans, the Persians, and the Egyptians; but in the religious system of the Druids, the belief in this mystery was given a peculiar prominence, and far from there being anything uncommon in the erection of such an altar as that of Chartres, we are assured by more than one author that they were of frequent occurrence not only in Gaul, but also in Germany and England.

Whatever may have been the source whence the Druids obtained this fragment of primeval truth,

it cannot be doubted that the possession of it prepared them in some sort for receiving the doctrine of the

Incarnation when first preached to them by Christian apostles. Hence, when St. Polentianus and

St. Savinianus arrived in the territory of Chartres, they found the minds of the inhabitants readily

disposed to accept the preaching of the gospel. As St. Paul appealed to the altar erected by the Athenians

to the unknown God, when declaring to them Him Whom they had ignorantly worshiped, so now the Christian missionaries

found willing hearers when they announced themselves servants of Him Who had truly been born of the Virgin they had

so long by anticipation revered. And on the conversion of the Chartrains, nothing could be more natural than that

their ancient grotto should be transformed into a Christian temple dedicated in honor of the true Mother of God.

(Even this title is said to have not been unknown to the Druids. Guibert de Nogent tells us in his memoirs that

the church of his monastery was said to have been erected on the site of one of the sacred woods of the Druid priests,

where they had been used to sacrifice to the Mother of the God Who was to be born – Matri futurae DEI nascituri. –

Guib. ‘de Vita sua’, lib. 2 c. 1.) Nor can it be said that these facts rest only on tradition.

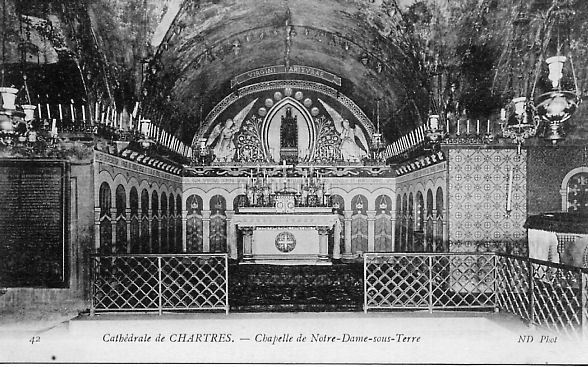

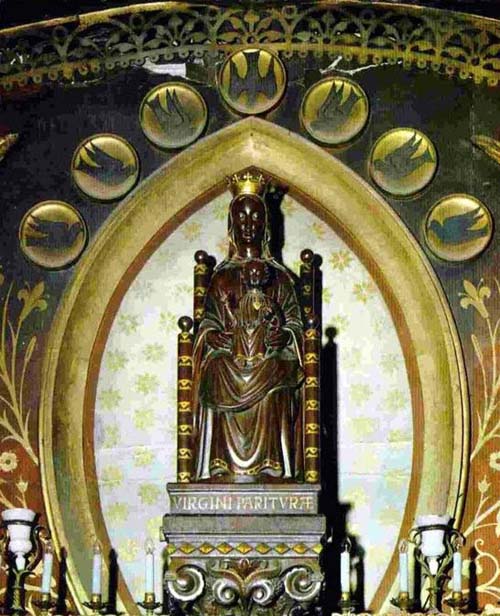

The grotto still forms the crypt of the present cathedral, and has been religiously preserved through

all the reconstructions of the edifice; and up to the disastrous period of the revolution the ancient

Druidical statue was venerated there, forming one of the greatest treasures of the city, whether we regard it

from a religious or merely an antiquarian point of view. It was most unhappily destroyed by the

'worse than Vandals' who at that time busied themselves in profaning every sacred monument;

but a very exact description of it has been preserved, from which we learn that it was carved in wood,

and (as it would seem) out of the trunk of a tree; that it was black with extreme age, and that it represented

the Virgin sitting in a chair and holding Her Divine Child on Her knee (this image has since been replaced by a

replica – image left).

Whatever may have been the source whence the Druids obtained this fragment of primeval truth,

it cannot be doubted that the possession of it prepared them in some sort for receiving the doctrine of the

Incarnation when first preached to them by Christian apostles. Hence, when St. Polentianus and

St. Savinianus arrived in the territory of Chartres, they found the minds of the inhabitants readily

disposed to accept the preaching of the gospel. As St. Paul appealed to the altar erected by the Athenians

to the unknown God, when declaring to them Him Whom they had ignorantly worshiped, so now the Christian missionaries

found willing hearers when they announced themselves servants of Him Who had truly been born of the Virgin they had

so long by anticipation revered. And on the conversion of the Chartrains, nothing could be more natural than that

their ancient grotto should be transformed into a Christian temple dedicated in honor of the true Mother of God.

(Even this title is said to have not been unknown to the Druids. Guibert de Nogent tells us in his memoirs that

the church of his monastery was said to have been erected on the site of one of the sacred woods of the Druid priests,

where they had been used to sacrifice to the Mother of the God Who was to be born – Matri futurae DEI nascituri. –

Guib. ‘de Vita sua’, lib. 2 c. 1.) Nor can it be said that these facts rest only on tradition.

The grotto still forms the crypt of the present cathedral, and has been religiously preserved through

all the reconstructions of the edifice; and up to the disastrous period of the revolution the ancient

Druidical statue was venerated there, forming one of the greatest treasures of the city, whether we regard it

from a religious or merely an antiquarian point of view. It was most unhappily destroyed by the

'worse than Vandals' who at that time busied themselves in profaning every sacred monument;

but a very exact description of it has been preserved, from which we learn that it was carved in wood,

and (as it would seem) out of the trunk of a tree; that it was black with extreme age, and that it represented

the Virgin sitting in a chair and holding Her Divine Child on Her knee (this image has since been replaced by a

replica – image left).

It was in 1020 that the celebrated Bishop Fulbert of Chartres first formed the design of replacing the

simple wooden church erected over the sacred grotto in primitive times, by a more solid structure.

The cathedral begun by him was, however, destroyed by fire while still incomplete, and the whole work had to be

recommenced in the reign of Philip Augustus. The extraordinary scenes which then took place have been recorded

by contemporary writers, such as Hugh, Archbishop of Rouen, whose letter to the Bishop of Amiens is still preserved,

wherein he speaks of those marvels, the rumor of which has spread into all parts, and inspired the population of other

dioceses with similar zeal. It was at Chartres,

he says, that men were first seen humbly dragging carts

and other conveyances to help in the construction of a church, their humility being rewarded by miracles.

He goes on to relate that his own people having visited Chartres and beheld what was done there returned to Rouen,

determined not to be outstripped in devotion by their neighbors. Having resolved to admit none into their society

save those who had confessed their sins, and were living at peace with their neighbors, they elected one of their

number as chief, and under his direction undertook the restoration of their cathedral church, harnessing themselves

like dumb animals to heavy carts, imposing on themselves severe privations, and performing all their labors in silence

and tears.

Robert du Mont speaks in like manner of the spectacle first witnessed at Chartres where women as well as men were to be

seen laboring like beasts of burden. He who has not beheld these things,

he says, will never see their equal...

Everywhere there is penance, humility, and forgiveness of injuries; men and women dragging themselves on their knees

through mud and marsh, beating their breasts, and calling on Heaven in the midst of innumerable miracles that elicit

songs of thanksgiving.

But the most striking description is that given by Haymon, Abbot of St. Pierre-sur-Dives,

who wrote a history of the miracles performed through the intercession of the Blessed Virgin Mary in 1140,

in which he relates the scenes of which he had been an eyewitness during the construction of his own abbey church,

on which occasion thousands both of men and women emulated the example of the people of Chartres,

coming from great distances, across mountains and even rivers, harnessed to their wagons, everywhere preserving perfect order,

singing canticles in admirable concert, or imploring the mercy of God on their sins.

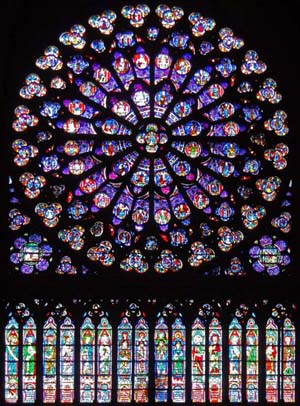

The dedication of the cathedral of Chartres took place in 1260, in the presence of the good king St. Louis,

who at his own expense erected the southern porch. This venerable structure is admitted to be one of the grandest

ecclesiastical monuments existing in France; nevertheless it owes its celebrity far less to the beauty of its

architecture than to the sacred relics which have for centuries attracted the devotion of the faithful.

Of these the Druidical statue, or Notre Dame de Sous-Terre, was formerly the most renowned.

The massive crypt erected by Fulbert was not destroyed with the rest of the building; and in constructing it

he was careful not to disturb the ancient grotto and its image, in order, as one writer expresses it,

not to dry up a fount of grace.

In course of time the piety of the faithful enriched this grotto

with every kind of ornament, and in the seventeenth century its walls blazed with gold and precious marbles

lighted up by innumerable lamps, which burnt day and night before the sacred image.

Another image stood in the upper church known as Our Lady of the Pillar (image right),

which was saved from destruction at the time of the revolutionary troubles and has been restored to its former place;

but the third and most precious of the Chartres treasures was the relic known as Our Lady's veil,

which was long preserved at Constantinople, and is supposed to have been presented to Charlemagne by the Empress Irene,

and afterwards to have been brought from Aachen to Chartres by his grandson, Charles the Bald.

This relic, folded in another silken veil, was formerly kept in a cedar reliquary, adorned with gold and jewels,

which was never opened, and the reliquary itself was only exposed for veneration on extraordinary occasions.

Another image stood in the upper church known as Our Lady of the Pillar (image right),

which was saved from destruction at the time of the revolutionary troubles and has been restored to its former place;

but the third and most precious of the Chartres treasures was the relic known as Our Lady's veil,

which was long preserved at Constantinople, and is supposed to have been presented to Charlemagne by the Empress Irene,

and afterwards to have been brought from Aachen to Chartres by his grandson, Charles the Bald.

This relic, folded in another silken veil, was formerly kept in a cedar reliquary, adorned with gold and jewels,

which was never opened, and the reliquary itself was only exposed for veneration on extraordinary occasions.

The people therefore formed their own ideas as to the nature of the relic, which commonly went by the

name of la chemise de Notre Dame (the shirt of Our Lady), and the custom was introduced of fashioning garments

supposed to resemble in form the veil so religiously preserved, which were laid on the reliquary and afterwards

sold to pious pilgrims. Nobody ever thought of visiting Chartres without bringing away one of the

chemisettes de Notre Dame. They were supposed to afford an excellent defense in battle,

and among other brave knights who were proud to wear them, was the chevalier sans peur et sans reproche

(knight without fear and without reproach), who came to Chartres, says his biographer, pour se faire enchemiser

de la chemisette de Notre Dame (to be clothed in the little shirt of Our Lady).

Even in 1712, when in consequence of the decay of the cedar-wood reliquary, it became necessary

to transfer the holy relic to a silver case, this appears to have been done without any examination of the relic itself,

which was not taken out of its silken covering.

In 1793, however, that which had for nine centuries been an object of such pious veneration fell into the hands of the revolutionary government. Some of their commissaries were dispatched to Chartres in the December of that year, who, entering the sacristy of the cathedral, insisted on having the case containing Our Lady's veil given up to them. When however they found themselves in presence of it, they were seized with a certain involuntary sentiment of fear, and strange to say, they shrank from laying their own hands on the relic, and decided that the case should be opened by a priest. When this was done, and the veil was withdrawn from its covering it was found to be wholly unlike what they had expected to see. In the hopes of proving the falsehood of the tradition attached to it, by exposing the popular delusion as to its form and character, the commissaries cut off a considerable portion of it and sent it to the celebrated Oriental scholar, the Abbé Barthélemy, whose learning had been respected by the revolutionaries themselves, and had recently procured his release from prison, after he had narrowly escaped becoming a victim of the September massacres.

The Abbé was not informed whence the fragment had been obtained; but after a careful scientific examination, he replied that it was of great antiquity, and probably as much as two thousand years old, and that it appeared to have formed part of a veil or external wrapping, covering the head and entire person, similar to those still worn by women in the East. This decision, procured by those whose object it had been to destroy all popular faith in the genuine character of the relic, was the greatest confirmation of its authenticity that could have been given, and the commissaries thought it wise to proceed no further. They left the veil in its case, contenting themselves with plundering the sanctuary of all its treasure, and causing the Druidical image to be publicly burned before the west door of the cathedral.

Occasion was unfortunately taken of the opening of the reliquary to cut up the precious veil, and distribute its fragments in various quarters. A large portion found its way into Brittany, where it is now preserved in the church of St. Anne d'Auray. Other smaller fragments were carried by missionary and emigrant priests into Canada and England. On the re-establishment of religion, however, Mgr. de Labersac, Bishop of Chartres, caused all the pieces he could collect to be carefully authenticated and deposited in a new silver reliquary, which in 1822 was restored to the cathedral treasury.

It need hardly be said that the sanctuary which possessed so many memorials of the devotion to

Our Lady has always been regarded with special veneration. The number of graces granted within its walls

have formed the subject of histories both in prose and verse, and few cities have boasted with better cause

than Chartres of the singular protection afforded them by their heavenly patroness. Thus in 911 when the city

was besieged by the Normans, under their chief Rolla, and on the point of falling into their hands,

we read that the Bishop of Chartres advanced into the midst of the combatants carrying the sacred veil,

and that at his approach the Normans fled, being seized with a sudden panic. A little chapel may still

be seen erected at the time on the spot where this occurrence took place. It stands in a ravine near

the city which received the name of Val-rollon, now corrupted into Vauroux,

and the meadows through which the Norman chief beat his retreat were designated the Prés des reculées

(near the ravines).

It need hardly be said that the sanctuary which possessed so many memorials of the devotion to

Our Lady has always been regarded with special veneration. The number of graces granted within its walls

have formed the subject of histories both in prose and verse, and few cities have boasted with better cause

than Chartres of the singular protection afforded them by their heavenly patroness. Thus in 911 when the city

was besieged by the Normans, under their chief Rolla, and on the point of falling into their hands,

we read that the Bishop of Chartres advanced into the midst of the combatants carrying the sacred veil,

and that at his approach the Normans fled, being seized with a sudden panic. A little chapel may still

be seen erected at the time on the spot where this occurrence took place. It stands in a ravine near

the city which received the name of Val-rollon, now corrupted into Vauroux,

and the meadows through which the Norman chief beat his retreat were designated the Prés des reculées

(near the ravines).

A still more celebrated event was the deliverance of the city from the army of Edward III, who was encamped outside the walls in 1360, when the people having solemnly invoked the intercession of the Blessed Virgin, that tremendous tempest broke out so graphically described by Froissart, wherein a thousand men-at-arms and six thousand horses were killed by monstrous hailstones. Then it was that Edward, falling on his knees, stretched out his arms in the direction of the cathedral, and in his turn implored the aid of Our Lady of Chartres, vowing if his army were spared, that he would grant peace to France. Hardly was his vow pronounced than the storm abated, and in fulfillment of his promise, the king soon after signed the treaty known as the Great Peace of Bretigny.

Two centuries later, in 1568, a Huguenot army was at the gates of Chartres, headed by the Prince of Condé,

who had been proclaimed king by the insurgent heretics. The citizens in preparing for the defense had placed over

each of their gates a statue of the Blessed Virgin, bearing the inscription Carnutum Tutela (Protectress of Chartres).

One of these statues appeared over the Porte Drouaire, and against it the Huguenots directed a furious cannonade,

which broke down the whole of the surrounding walls, but left the image itself untouched.

The besieged defended themselves gallantly, and one piece of artillery which had been taken

from the Protestants at the battle of Dreux, and which bore in consequence the title of the Huguenot,

did such good service on this occasion that it was afterwards rechristened the good Catholic.

The assailants however succeeded in effecting a breach between the Porte Drouaire and the River Eure,

and the citizens believing all human chance of escape was over, betook themselves in crowds to the subterranean grotto,

to implore the protection of Notre Dame de Chartres. Wonderful to relate, at the very moment when their victory seemed secure,

the besieging army withdrew from the open breach, and raised the siege. Chartres was once more delivered,

and not by the force of arms; and in commemoration of this event an inscription was put up still to be seen

in the public library; a little chapel being also erected on that part of the wall which had been destroyed

by the artillery of the enemy, bearing the title of Notre Dame de la Brêche (Our Lady of the Breach).

An annual procession was made to this chapel, which in 1789 was sold and demolished.

It was however rebuilt in 1844, and the annual procession of gratitude was restored.

Two centuries later, in 1568, a Huguenot army was at the gates of Chartres, headed by the Prince of Condé,

who had been proclaimed king by the insurgent heretics. The citizens in preparing for the defense had placed over

each of their gates a statue of the Blessed Virgin, bearing the inscription Carnutum Tutela (Protectress of Chartres).

One of these statues appeared over the Porte Drouaire, and against it the Huguenots directed a furious cannonade,

which broke down the whole of the surrounding walls, but left the image itself untouched.

The besieged defended themselves gallantly, and one piece of artillery which had been taken

from the Protestants at the battle of Dreux, and which bore in consequence the title of the Huguenot,

did such good service on this occasion that it was afterwards rechristened the good Catholic.

The assailants however succeeded in effecting a breach between the Porte Drouaire and the River Eure,

and the citizens believing all human chance of escape was over, betook themselves in crowds to the subterranean grotto,

to implore the protection of Notre Dame de Chartres. Wonderful to relate, at the very moment when their victory seemed secure,

the besieging army withdrew from the open breach, and raised the siege. Chartres was once more delivered,

and not by the force of arms; and in commemoration of this event an inscription was put up still to be seen

in the public library; a little chapel being also erected on that part of the wall which had been destroyed

by the artillery of the enemy, bearing the title of Notre Dame de la Brêche (Our Lady of the Breach).

An annual procession was made to this chapel, which in 1789 was sold and demolished.

It was however rebuilt in 1844, and the annual procession of gratitude was restored.

The pilgrimages to Notre Dame de Chartres were in olden times so numerously attended, and especially on the Feast of Our Lady's Nativity, that it is said the city could not afford shelter to one half of the pilgrims, multitudes of whom spent the night in the cathedral. The sensible inclination of the floor of the nave from the choir towards the door is attributed to the constant influx of worshipers, and their vigils in the church not being very conducive to the cleanliness of the building, it was found necessary to flood the pavement every morning before the celebration of Mass; a cistern being constructed close by for this purpose, the old pipe of which was much later discovered.

The reader will perhaps smile at this last illustration of the devotion exhibited towards this ancient sanctuary, and take it as a proof that the pilgrims to Chartres in former times presented that combination of dirt and piety which is no uncommon spectacle in Catholic churches. In other words, the sanctuary of Chartres was beloved and resorted to by the poor, and within its walls they truly felt themselves at home. But if this were true, it is no less certain that the list of her pilgrims includes likewise the most illustrious names of Europe: three Popes, almost every one of the kings of France, several even of those of England, together with her saintly primates St. Anselm and St. Thomas Becket, as well as St. Bernard, St. Vincent de Paul, and St. Francis de Sales, and lastly, among the queens of France, the beautiful and unfortunate Mary Stuart (Queen of Scots). Visitors of this class enriched the church with their splendid ex-voto offerings, the inventory of which, in 1682, filled a quarto volume of 170 pages. There you might see the silver scepter of John II, the golden image of the Blessed Virgin offered by his namesake, John, Duke of Berry, the magnificent cross blazing with emeralds and rubies presented by Henry III, and the rich reliquaries and other gifts offered by Henry IV, who chose that the ceremony of his coronation should take place within this cathedral.

But all these treasures disappeared in the pillage which took place during the revolutionary crisis, and even after the restoration of religion the cathedral continued to bear lamentable traces of the desecration then perpetrated. It has been reserved to our own days (the 19th century) to witness the noble efforts of the Bishop of Chartres, assisted by the pious devotion of his flock, exerted in restoring the venerable sanctuary to something of its former grandeur, the thirteen chapels of the cathedral raised from their ruins, the grand old crypt cleared out, and again thronged by pilgrims to the subterranean grotto, whilst Our Lady of the Pillar fills Her old place in the upper church, and daily beholds at Her feet a crowd of pious worshipers.

Among those whose prayers and example have done much to effect this striking revival of faith in the hearts of the people,

must be numbered the venerable prelate, Monseigneur Clausel de Montals, late Bishop of Chartres.

On first coming to the diocese, he engaged himself by vow to spend half an hour every Saturday in

prayer before Our Lady of the Pillar, and during the whole of his long episcopate he was never known

to fail in accomplishing his promise. Neither extreme old age nor painful infirmities sufficed as an

excuse for his absenting himself, and when at last obliged to resign his episcopate charge,

he failed not in his act of resignation to express his desire of being suffered to die

at the foot of those towers which crown the Sanctuary of Our Lady.

His wish was almost literally accomplished,

for, on the 3rd of January, 1857, finding himself too feeble to make his way to the cathedral on foot,

he caused himself to be carried thither by his attendants to make what proved to be his farewell visit

to his favorite sanctuary, and on the following day he happily expired at the age of 88.

NEW: Alphabetical Index

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com