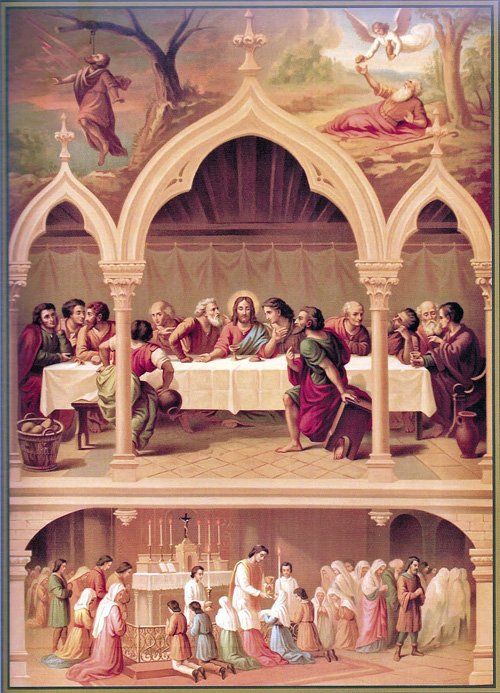

A. The Holy Eucharist was instituted both as a Sacrament and a Sacrifice.

A. The Holy Eucharist was instituted both as a Sacrament and a Sacrifice. A. The Holy Eucharist was instituted both as a Sacrament and a Sacrifice.

A. The Holy Eucharist was instituted both as a Sacrament and a Sacrifice.

This Sacrament is unique in this – that it is at the same time a Sacrifice. It is a Sacrament because it sanctifies the soul of its own efficacy; it is a Sacrifice inasmuch as it is an oblation of a visible gift to God's honor and glory.

The Holy Eucharist as a Sacrament differs from the other Sacraments in this – that it consists not only in a passing action, but in a permanent state of existence. Considered in its permanent state it is the true Body and the true Blood of Jesus Christ – truly, really, and substantially present under the appearances (species) of bread and wine for the nourishment of our souls. Regarded as an action, or in the instant of its origin, it is the changing of bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ. In this change, in which Christ presents Himself a Victim to His Heavenly Father, consists the sacrifice.

In its permanent state the Holy Eucharist (from a Greek word meaning good gift or thanksgiving) is sometimes called the Sacrament, by way of excellence – the Sacrament of the Altar, the Blessed Sacrament, Holy Communion, the Body of Christ, etc. Considered as an action, we call it the Holy Sacrifice – the Sacrifice of the Mass. The names Sacrament of the Altar and Holy Eucharist also point to its sacrificial character.

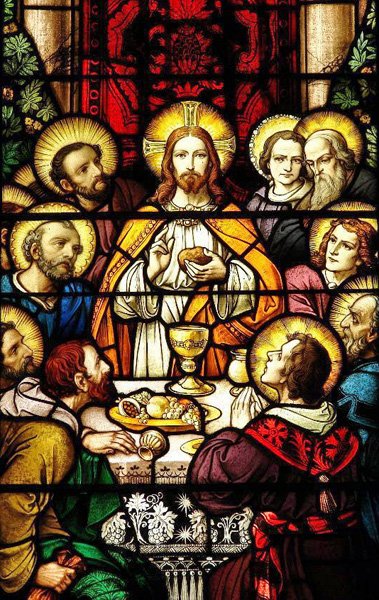

Christ instituted the Holy Eucharist together with the Sacrifice of the New Law (promised in John 6)

when, on the eve of His Passion, He took bread and blessed it and gave it to His disciples, saying: Take ye and eat,

this is My Body;

and in like manner taking a chalice with wine, He blessed it and gave it to His disciples, saying:

Drink ye all of this; for this is My Blood of the New Testament, which shall be shed for you and for many unto the

remission of sins.

Do this in remembrance of Me.

(Matt. 26: 26-28; Mark 14: 22-24; Luke 22: 19-20;

1 Cor. 11: 23 et seq.)

B. Jesus Christ is truly, really, and substantially present in the most Holy Sacrament of the Eucharist.

Truly, really, and substantially (vere, realiter, et substantialiter) are the words of the Council of Trent (Sess. 13 can. 1). He is truly present – not merely under a sign or symbol, as Zwingli and other heretics asserted. He is really present – not merely in virtue of our belief or imagination, as Luther and his followers asserted. He is substantially present – not merely by His works or effects, as Calvin and other heretics taught.

I. Scripture offers abundant proofs of the real presence.

a. Christ promised it in express terms: Amen, amen, I say unto you: Except you eat the Flesh of the Son

of man and drink His Blood, you shall not have life in you. He that eats My Flesh and drinks My Blood has everlasting life

(John 6: 54-55). Our Lord does not here mean to inculcate the necessity of faith in Himself, of a

figurative eating and drinking. For to eat the flesh of another had not, among the Jews, this figurative

meaning; if used figuratively it signified to inflict injury. Therefore these words cannot be taken in a figurative,

but in their literal sense; for Christ certainly did not wish His disciples to inflict an injury upon Him.

The Jews and the disciples themselves understood the words in their literal sense; and Christ confirmed them in this opinion by appealing to His Divinity, to which all things are possible (John 6: 63), and by rebuking their unbelief and their carnal views, which were unwilling to understand what is spirit and life – what is spiritual and supernatural (John 6: 64).

b. The words which refer to the institution itself of the Holy Eucharist are no less evident:

This is My Body... this is... My Blood...

These words, since they cannot be taken in a figurative sense,

must have been meant literally. If Christ had not, in virtue of these words, given us His Body and Blood for the

nourishment of our souls, but merely bread and wine as a symbol of His Body and Blood, He would have been the cause of

universal idolatry for centuries. Therefore, as from the simple fact that He called Himself the Son of God we conclude

His Divinity, because He could not have invincibly led His followers into idolatry, we must believe that He gives us His

true Body and Blood – that He is really present in the Holy Eucharist.

c. The words referring to the reception of the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ are likewise an

invincible evidence of His real presence. The chalice of benediction, which we bless, is it not the communion of the

Blood of Christ? And the bread which we break, is it not the partaking of the Body of the Lord? For we, being many,

are one bread, one body, all that partake of one bread. Behold Israel according to the flesh: are not they that eat

of the sacrifices partakers of the altar?

(1 Cor. 10: 16-18). As truly, therefore, as the Israelites partook

of their sacrifices, which were only types of the sacrifice of Christ, so truly do we partake of the Body and Blood of Christ.

Again: Whosever shall eat this bread, or drink the chalice of the Lord unworthily, shall be guilty of the Body and the Blood

of the Lord. But let a man prove himself, and so let him eat of that bread and drink of the chalice

(1 Cor. 11: 27-28).

As the Israelites, if they ate the manna in the desert in the state of mortal sin, although it was a figure of Christ,

would not thereby commit a sin, neither would the faithful be guilty of the Body and the Blood of the Lord by receiving

this spiritual food in the state of mortal sin, if what they received were only a figure of the Body and Blood of Christ.

II. The Tradition of the Church is no less explicit on the real presence of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament.

II. The Tradition of the Church is no less explicit on the real presence of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament.

1. The earliest fathers bear witness to the real presence of Christ in the Holy Eucharist.

St. Ignatius † 108 (epist. ad Smyrn. n. 7) says: [The Docetae] abstain from the Holy Eucharist and prayer because

they do not believe that the Eucharist is the Flesh of Our Lord Jesus Christ, Who suffered for our sins, and Whom the Father

raised to life again.

These heretics, therefore, differed in this point from the universal belief of the Church.

Therefore the universal belief of the Church was that the Flesh of Jesus Christ was really present. St. Justin † 165,

in his Apologia (I. 66) declares that the Christians in their meetings do not, as the pagans falsely accused them,

eat the flesh of a child, but that the consecrated food they receive is the Flesh and Blood of Jesus, God made Flesh.

St. Irenaeus † 202 (adv. haeres. 5 c. 2) writes: Christ declares that the chalice, which is but earthly,

is His own Precious Blood. Since, then, the chalice and the bread by the word of God become the Eucharist of the

Body and Blood of Christ, how dare they [the heretics] deny that the flesh which partakes of the Flesh and Blood of Christ,

and is a member of Him, will receive the gift of God, i.e., life everlasting?,

Tertullian † 160, proposes the Churchs

teaching on this point in several passages of his writings (some of which were quoted in the last article on Confirmation).

St. Augustine † 430 (in ps. 33, I 10), not to mention many other fathers, asks: Who can hold himself in his own

hands? A man may be held in the hands of another; but no man can hold himself in his own hands.

He answers:

Christ held Himself in His own hands when He gave His Body to His disciples, saying: This is My Body; for that was the

Body which He held in His hands.

If Christ had borne only the figure of His Body in His hands, St. Augustine could

not doubt that another could do the same.

2. In the most ancient liturgies we find evident expressions of the belief in the real presence.

Thus we read in the liturgy of Jerusalem, which at least in its essential parts dates back to the time of St. James:

Let us dismiss all worldly thoughts from our minds, for the King of kings, the Lord of hosts, Christ, our God,

is about to be sacrificed and to be given to the faithful as their food.

In the liturgy which bears the name of

St. Basil † 379, God is besought to make of this bread the true and Precious Body of Jesus Christ, Our Lord, God,

and Savior, and from this wine His true and Precious Blood, which was shed for the salvation of the world.

3. All the Eastern sects which from the earliest times have been separated from the Church's communion have preserved the belief in the real presence. Consequently, it must have existed in the Church at the time of their separation.

4. The very fact that this universal belief at any time existed in the Church is sufficient proof that it is apostolic doctrine. Such a new dogma could not have been introduced in the Church without great opposition, of which there would be some account in history. But in history we find no trace of such a fact: on the contrary, we find the universal belief in the real presence in every age: and when in the eleventh century the heretic Berengarius denied this dogma the whole Church was horrified at the innovation.

III. The real presence of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament is altogether consistent with the character of Christianity.

1. Christianity contains the reality of what the Old Law prefigured and foreshadowed.

The Old Law prefigured the habitation of God among men. God was present in a figure. I will appear in a cloud

over the oracle

(Lev. 16: 2). In order to realize this figure God wished to dwell on our altars really

and truly as the Word made Flesh.

2. Christianity satisfies the yearnings of the soul for God as far as this is possible in the present life. Man naturally desires to have God near to him, and, as far as may be, in visible form. The greater his love the greater is his longing, since love desires to be with the beloved. Now, to gratify this desire of the human heart God vouchsafed to dwell amongst us visibly, but in such a way that we might still have the full merit of Faith.

3. Christianity is the consummation of the divine scheme of our salvation, and, as it were, a foretaste of that eternal life which consists in intimate union with God. Therefore it is meet that in our present state we should enjoy a special visible presence of God in our midst. Otherwise the condition which began with the coming of Christ would have ceased, and made room for a dreary state of desolation and abandonment.

Once the fact of the real presence is established, there is no need of reasons to prove its possibility. What may be said in regard to the Holy Trinity applies also to this mystery: as a mystery we cannot positively prove its possibility by reason – we can only know it by revelation. Reason, however, can negatively prove the possibility of a mystery, by showing that the arguments against it are futile. If, for instance, it be objected that it is impossible for Christ to be in several places at once, we must distinguish between the natural and the supernatural mode of presence of a body. Reason tells us that God is present in all places at the same time, and that our soul is entirely present in each part of the body. Why should not the glorified Body of Christ, which enjoys a higher, spiritual mode of existence, be able to multiply its presence?

C. Christ is present in the Blessed Sacrament by transubstantiation, i.e., by the change of the entire

substance of bread and wine into His Body and Blood.

C. Christ is present in the Blessed Sacrament by transubstantiation, i.e., by the change of the entire

substance of bread and wine into His Body and Blood.

Thus the presence of Jesus Christ in the Holy Eucharist is defined by the Council of Trent (Sess. 13 can. 2; ib. c. 4). Therefore Christ is not present in, or with, or under the substance of bread and wine, as Luther and his followers maintained; but that which before was bread becomes in virtue of consecration the true Body and Blood of Christ. It is only the species of bread and wine that remain, i.e., those external appearances that come under the senses; under these appearances Christ Himself is present. These species, however, are not the species of the Body and Blood of Christ, as if the Body and Blood of Christ assumed the shape, taste, etc., of bread and wine. Christ is present in His own glorious mode of existence, but under the outward semblance of foreign substances.

I. The bread and wine are changed into the Body and Blood of Christ.

a. That a real change does take place follows from the words of Christ: This is My Body; this is... My Blood... (for the sake of brevity, we omit the remainder of the words of Consecration). The demonstrative this points out what He gave to His disciples under the appearance of bread and wine. If it were only bread and wine – if Christ had been present only in, or with, or under the substances of bread and wine, He could not say simply: This is My Body; but rather: This bread is My Body, which would be manifestly false; or He would have said: In or with, or under this bread is My Body. Moreover, if the bread and wine were not really changed into the true Body and Blood of Christ, He could not have said: This is My Body, which is given for you (Luke 22: 19); and: This is My Blood, which shall be shed for many unto the remission of sins (Matt. 26: 28). Christ, in fact, did not offer bread, or shed wine on the Cross; but He sacrificed His true Body, and poured out His true Blood.

No one would venture to take a book or a stone in his hand and say: This is God. For, although God in virtue of His immensity is present in that book or stone, the word this points out the substance naturally underlying the sensible qualities of the book or stone. Nor would anyone pointing to another's hand say: This is your soul, although the soul is substantially united with the hand; for this demonstrates only what is sensibly manifested in the appearances of the hand. Therefore, if the substance of bread or wine had been present in any way whatever when Christ spoke those words He would have uttered a falsehood.

b. In the writings of the fathers we often meet with the expression that bread is made, or becomes, the Body of Christ; they distinctly assert that a change takes place. The same expressions occur in the most ancient liturgies of the Church.

II. The entire substance of bread and wine is changed into the Body and Blood of Christ – in other words the change takes place by transubstantiation.

a. It is the express teaching of the Council of Trent (ibid.) that the whole substance of bread and wine is changed, the appearances only remaining; which change is most aptly called transubstantiation. Hence all the integral as well as the essential parts of the bread and wine are likewise changed into the Body and Blood of Christ, since these parts either contain or constitute the substance of bread and wine. This change is, therefore, altogether sui generis (of its kind – a change of what kind of thing it is), as nothing of the former substance remains, but only the external appearances, which are accessory to the substance; whence it is very properly called transubstantiation.

b. The total change of substance follows likewise from these words: This is My Body; this is... My Blood... (1) These words can be true only when all the integral parts of the bread and wine are changed; for the demonstrative this points to all parts alike, and if a single part were not the Body or the Blood of Christ the proposition would not be true. (2) The essential parts constituting the bread and wine are changed or cease to exist; for they give place to an already existing substance – the Body and Blood of Christ – having its definite constituent elements, and admitting of no part or portion of that bread and wine. If anything of the substance of bread and wine remained, the Body and Blood of Christ as well as the bread and wine would be changed; nay, the Body and Blood of Christ would be subject to continual change, which is inconceivable.

The cessation of the substances, however, is not to be considered an annihilation, but a true change, inasmuch as it results not in nothing, but in another substance, and inasmuch as the species (appearances) of bread and wine remain the same after as before the change of substance.

That the species are something real, independently of our perception, follows from the nature of a Sacrament as a sensible sign, and therefore as an objective thing, independent of our senses (i.e. Christ is still really present even when in the tabernacle, where no one can see, taste, etc. the species). According to the common opinion, the species are the real accidents of bread and wine – those real, changeable, and sensible qualities naturally inherent in the species (such as color, shape, taste, smell, etc.), but distinct from them, which in this case are by God's omnipotence miraculously (or, more precisely, supernaturally) preserved without the substances themselves.

D. Christ continues to be present under the species of bread and wine as long as the species themselves

continue to exist.

D. Christ continues to be present under the species of bread and wine as long as the species themselves

continue to exist.

I. Christ gave Himself to His disciples with the words: This is My Body; this is... My Blood... What He gave them, therefore, existed at the moment when the words were spoken, and not merely, as the Lutherans assert, at the moment the disciples received it. Again, on what grounds could we believe that in the chalice, out of which the disciples drank one by one, there was now wine – while it was passed from one to another, now the Blood of Christ – while each one drank of it? If Christ was present under the species of bread and wine at the moment of consecration, there is no reason to think that He ceased to be present as long as the species remained. On the contrary, once He had determined to be present in virtue of the consecration under the appearances of bread and wine, we must rather conclude that as long as these appearances continue to exist, Christ also continues to be present.

II. The custom prevailing from the earliest times of preserving the Blessed Sacrament in churches, and during persecutions even in private houses; of bearing it to the sick, carrying it on journeys, etc. is an evident proof of the Church's belief in the continuous presence of Jesus Christ under the sacramental species. It is only in the assumption that Christ is continually present that St. Augustine could assert that Christ held Himself in His own hands.

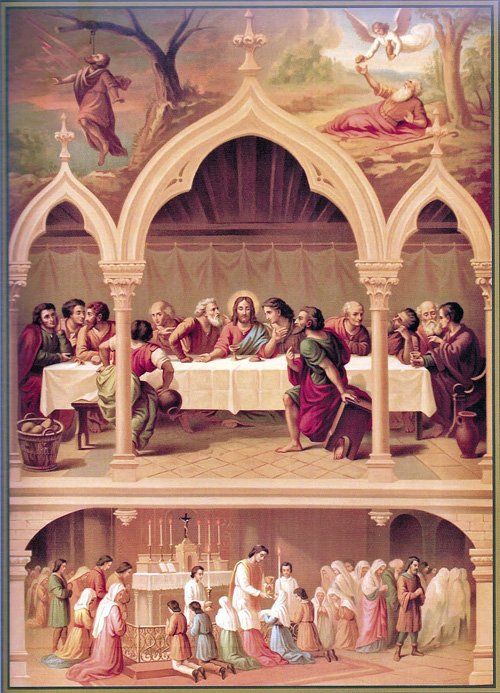

E. Christ is entirely present under each species and under each particle of either species.

I. Christ is entirely present – with His Flesh and Blood, His Body and Soul, His Humanity and Divinity under each species. Christ gave His disciples the same Body that He possessed, and on our altars bread is changed into the same Body which is now glorified in Heaven; for the words: This is My Body, would not be true, unless the bread were changed into the living Body of Christ as it now exists. But where the Body of the living Christ is, there is also His Blood, and His Soul, and His Divinity; and where His Blood is, there also is His Body, His Soul and His Divinity – the entire Christ.

In virtue of the words of consecration the bread is changed into the Body, and the wine into the Blood of Christ. But His Blood is present under the species of bread, and His Body under the species of wine, and His Soul under both species in consequence of the inseparable union between them. Again, with the human nature of Christ is hypostatically united the Second Person of the Blessed Trinity; and in consequence of this union His Divinity is always present with His Humanity, and therefore under both sacramental species.

II. Christ is wholly present in each particle of either species so that he who receives one particle of the Host receives the whole Christ. There can be no doubt that each of the Apostles who drank out of the one chalice received Christ entire. For, since the entire substance of bread and wine was changed into the Body and Blood of Christ, we must say that any particle, however small, as long as it bears the appearance of bread or wine, is the Body and Blood of Christ. Therefore the entire Christ is present in the Eucharist after, as well as before, the division (Council of Trent Sess. 13, c. 3).

Since the species of bread and wine are not the proper, but only the assumed species of the Body and Blood of Christ, what is done to the species cannot therefore be said to be done to the Body and Blood of Christ itself. If, for instance, the former are divided or broken, the Body of Christ is not thereby divided or broken. But as the Body of Christ exists permanently under the species, and is really present wherever the species are, it is actually borne from place to place, as are the species. We may rightly say, however, that the Sacrament is broken (fracto demum sacramento); for the species are an essential part of the Sacrament. From the fact that Christ is permanently present with His Humanity and Divinity in the Blessed Sacrament, not merely at the moment of communion, it follows that we are bound to adore Him under the sacramental species. For the duty of adoration arises from the fact, not from the manner, of His presence. We adore Christ in the Holy Eucharist as He is – with His Godhead and Manhood. Both are alike the object of our adoration, whilst the Divinity alone is the reason of our adoration. The Church's object in publicly exposing the Blessed Sacrament, bearing it in procession, and commemorating the Real Presence in special feasts, is to promote the adoration of Jesus Christ, Who is truly present in the Eucharist as the Dispenser of all graces.

F. Only bishops and priests have the power to change bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ.

I. It was only to the Apostles that Christ gave the charge: Do this for a commemoration of Me.

That the bishops, the successors of the Apostles, possess this power is manifest. But priests also have received it.

For Our Lord by these words ordained the Apostles priests by the very fact that He gave them the power to offer sacrifice,

which is the function peculiar to priests (Council of Trent Sess. 22 can. 2). Hence it follows that since others

besides the bishops have received the sacerdotal character in the Church, the words of Christ also apply to them.

Tradition removes every doubt on the matter, as it shows that from the earliest times, both in the East and in the West,

priests as well as bishops offered the Holy Sacrifice, and thus acted as ministers of this Sacrament.

II. Bishops and priests are the only ministers of the Sacrament. For the words above cited were addressed only to the

Apostles and their successors in the priesthood, not to the faithful at large. It is only the Apostles, not the

faithful, who are the dispensers of the mysteries of God

(1 Cor. 4: 1). That same tradition which teaches

that a layman or woman can validly baptize teaches also that only bishops and priests can validly consecrate the

Holy Eucharist. Moreover, the reasons for which Christ gave all without exception the power validly to administer Baptism,

do not exist in the case of the Blessed Eucharist, since it is not of the same necessity as Baptism. Deacons may,

with the permission of the Ordinary, administer the Sacrament after it is consecrated – distribute the Holy Communion –

but they have not the power to consecrate the Body and Blood of Christ.

G. The matter of the Sacrament of the Eucharist is wheat bread and genuine wine of the grape; the form is

based on the words of Christ spoken at the Last Supper:

G. The matter of the Sacrament of the Eucharist is wheat bread and genuine wine of the grape; the form is

based on the words of Christ spoken at the Last Supper: For this is My Body

; For this is the Chalice of My Blood

of the new and eternal covenant; the mystery of faith, which shall be shed for you and for many unto the forgiveness of sins.

I. That Christ instituted wheat bread and wine of the grape as the matter of this Sacrament

is manifest from the Gospels, which speak simply of bread and wine, and describe the latter, moreover, as the fruit of the

vine

(Matt. 26: 29); while in the Oriental idioms bread without further qualification signifies wheat bread.

Leavened bread, which is used in the Greek Church, as well as unleavened bread, which is employed in the Latin Church –

Christ Himself consecrated unleavened bread, it being the day of the Pasch (Matt. 26: 17) – is valid matter;

for both are substantially bread (Council of Florence decr. union.) This twofold matter of bread and wine, however,

constitutes but one Sacrament, just as food and drink make up but one meal.

Bread and wine were chosen to signify that as food and drink nourish the body, so the Eucharist nourishes the soul. These elements at the same time illustrate the mystery of transubstantiation; since the food and drink we take is changed into our substance, there is no repugnance that bread and wine should by the power of God be changed into the Body and Blood of Christ.

II. It is in virtue of the form of this Sacrament, given above, that the priest, assuming the person of Christ and using the same ceremonies, changes the bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ. For it was in virtue of the words Christ spoke at the Last Supper that He changed the bread and wine into His own Body and Blood – and the sacramental form consists mainly in those words of Christ recorded by the Evangelists. It is these words, therefore, that give efficacy to the action and must be regarded as the form.

While all theologians have agreed that no words of the form should ever be excluded, there have been some who

thought that only the words, This is My Body... this is My Blood

were absolutely necessary. However, this view is no

longer tenable in light of the teaching of Pope Leo XIII, who in 1896, defining that Anglican orders are invalid, wrote:

All know that the Sacraments of the New Law, as sensible and efficient signs of invisible grace, ought both to signify

the grace which they effect and effect the grace which they signify. Although the signification ought to be found in the

whole essential rite, that is to say, in the matter and form, it sill pertains chiefly to the form, since the matter is that

which is not determined by itself, but which is determined by the form...

(Apostolicae curae). Now the words

This is My Body... this is My Blood,

taken alone, do not signify the grace effected by the Holy Eucharist,

but only transubstantiation. Speaking of the consecration of the wine, St. Thomas Aquinas taught (centuries earlier):

It must be said that all the aforesaid words belong to the substance of the form; but by the first words, This is the

chalice of My Blood, the change of the wine into Blood is denoted... but by the words which come after is shown the power

of the Blood shed in the Passion, which power works in this Sacrament, and is ordained for three purposes. First and

principally for securing our eternal heritage, according to Heb. 10: 19 : Having confidence in the entering into the holies

by the Blood of Christ; and in order to denote this, we say, of the New and Eternal Testament. Secondly for

justifying by grace, which is by faith according to Rom. 3: 25, 26: Whom God hath proposed to be a propitiation, through

faith in His Blood... that He Himself may be just, and the justifier of him who is of the Faith of Jesus Christ;

and on this account we add, the Mystery of Faith. Thirdly, for removing sins which are the impediments to both of

these things, according to Heb. 9: 14: The Blood of Christ... shall cleanse our conscience from dead works, that is,

from sins; and on this account, we say, which shall be shed for you and for many unto the forgiveness of sins

(Summa Theol. Pt. III q. 78 art. 3).

H. The chief effects of the Holy Eucharist are: increase of sanctifying grace, special actual graces, remission of venial sins, preservation from grievous sin, and the confident hope of eternal salvation.

I. The Holy Eucharist increases sanctifying grace. For, sanctifying grace being the foundation of the spiritual life, every increase of the spiritual life implies an increase of sanctifying grace itself. The increase of grace received in the Eucharist is unlike that imparted by the other Sacraments; for in this Sacrament it is Christ Himself, the source of all graces, Who becomes the food of our souls.

II. The Holy Eucharist gives us those actual graces necessary to maintain the spiritual life. It gives us the grace to practice the various virtues which insure our advancement in the spiritual life.

III. It remits venial sins. For, since it increases the spiritual life and incites us to the practice of virtue, it disposes and enables us to perform those acts by which venial sins are remitted – charity and contrition.

IV. It preserves us from mortal sin; for it strengthens us against that languor and lukewarmness which leads to mortal sin; it secures for us abundant graces to resist temptations and a special protection of God in all dangers of the soul.

V. It gives us a pledge of eternal life and of a glorious resurrection. He that eateth My Flesh and

drinketh My Blood hath everlasting life; and I will raise him up on the last day

(John 6: 55). Everlasting life

is the outcome and reward of the life of grace on earth; therefore, since the Holy Eucharist confers grace in such abundance

it gives us the assurance of eternal salvation, provided we do not hinder its effects.

I. The obligation of receiving the Holy Eucharist rests on a necessity, not of means, but of precept.

1. The Holy Eucharist is not, like Baptism, necessary as a means of salvation. (a) Baptism

alone of the Sacraments has been declared by Christ to be necessary as a means of salvation for all. He that believeth and

is baptized shall be saved

(Mark 16: 16). He saved us by the laver of regeneration, and the renewal of the

Holy Ghost

(Tit. 3: 5). (b) A thing is necessary as a means of salvation only when it confers a necessary

qualification for salvation. This Baptism certainly does, since it confers (for the first time) sanctifying grace,

without which it is impossible to enter upon the way of salvation; but the case is different in regard to the Holy Eucharist,

which indeed, like the other Sacraments, preserves and increases supernatural life, but does not, like Baptism, produce the

first grace in the soul. (c) This is manifestly the conviction of the Church, which, though it rarely administers the

Holy Eucharist to children under the age of discretion, never doubts of the salvation of those children who have received only

the Sacrament of Baptism (Council of Trent Sess. 21 c. 4; can. 4).

2. There exists, however, the obligation of receiving the Holy Eucharist in virtue of a divine precept.

Amen, Amen, I say to you: except you eat the Flesh of the Son of Man, and drink His Blood, you shall not have life in you

(John 6: 54). These words distinctly show the obligation of receiving the Eucharist; but it is an obligation

arising only from a divine command, since, as we have shown, it cannot be understood to be a necessary means of salvation.

All who have come to the use of reason are, therefore, bound by divine precept to avail themselves of this powerful means

of preserving and increasing the spiritual life of their souls. The law of the Church commands all who have attained to

the use of reason, and are sufficiently instructed, to receive the Holy Eucharist at least once a year, and that at Easter

time.

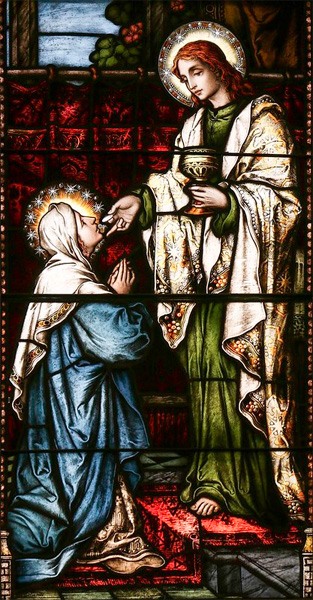

J. The Divine precept is fulfilled by receiving the Blessed Sacrament under only one species.

J. The Divine precept is fulfilled by receiving the Blessed Sacrament under only one species.

I. Those who receive the Holy Eucharist without actually celebrating the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass

(i.e., all except the priest) satisfy the Divine precept by receiving it under one kind. (a) Christ speaks

sometimes of the reception of His Body and Blood – under two kinds – and sometimes of the reception of His Body only –

under one kind – and to both manners of receiving He attaches the same graces: He that eateth this bread shall live forever

(John 6: 59). Hence the celebration of the Eucharist is described in the Scriptures simply as the breaking of bread

(Acts 2: 42; Luke 24: 30). (b) It by no means follows from the nature of the Sacrament that it is necessary to

partake of both kinds; but rather the contrary. For Christ is wholly present under either species, and both species

signify the full effect of the Sacrament – the nourishment of the soul. (c) Even in the earliest ages the Holy

Eucharist was for good reasons given under one kind, especially when administered outside the church or the celebration of

Mass; and in times of persecution, when it was kept in the houses of the faithful, and when preserved in the cells of hermits

in the desert, it was received under the species of bread only.

The Hussites – followers of John Huss – insisted on communion under both species; whence they were also called Calixtines or Utraquists. A chalice was the badge of their sect. Protestants in practice followed their example; but they differed from them in doctrine, for the Hussites believed in the real presence by transubstantiation, which Protestants denied.

II. For various reasons the Church in our times administers Communion under one species only.

The dignity of the Blessed Sacrament requires that the danger attending the preservation under both species (e.g., that of being spilled) be, as far as possible, prevented. Again, regard must be had to the faithful, of whom many might object to receiving under the species of wine, especially if administered to many communicants from the same chalice. Hence, the Greeks, who receive under both kinds, administer the Sacrament to the sick under the species of bread only. The solicitude for the purity of the faith made it imperative to administer Holy Communion under one kind, when heretics asserted the necessity of communion under both kinds. For the same reason Pope Leo the Great in the fifth century made it obligatory on all to receive Holy Communion under both species, when the Manichaeans refused to communicate under the species of wine.

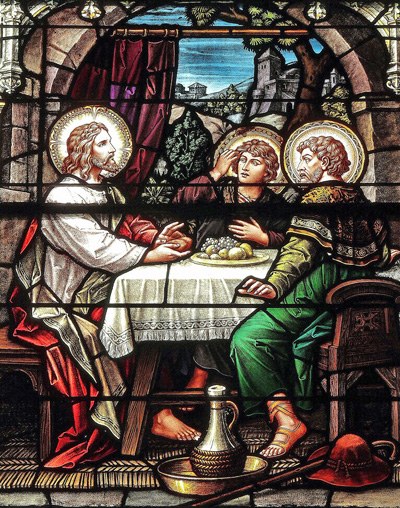

K. To receive the Blessed Sacrament worthily and becomingly a certain preparation, or disposition, is necessary.

I. The necessary preparation for the worthy reception of the Holy Eucharist extends both to the soul and to the body.

1. As the Holy Eucharist is a Sacrament of the living, in order to receive it worthily the soul

must be in the state of grace. If one is conscious of grievous sin, it is not enough to make an act of perfect

contrition. For, as the Council of Trent (Sess. 13 c. 7) teaches, in that case, in accordance with the Church's usage,

it is necessary to worthily receive the Sacrament of Penance. Thus are to be understood the words of St. Paul: Let a man

prove himself, and so eat of that bread and drink of the chalice

(1 Cor. 11: 28). The sanctity of this

Sacrament requires that those who approach it should endeavor to assure themselves, as far as it is possible in this life,

that they are in the state of grace. But the best means of gaining this assurance is the reception of the Sacrament of

Penance, this being the ordinary way of reconciliation with God for those who have grievously sinned after Baptism.

Unworthy communion is a great crime, a horrible sacrilege. A sacrilege is the profanation,

or unworthy treatment, of a sacred object. As the gravity of sacrilege increases with the sanctity of the object profaned,

it is evident that to receive the Body of Christ – the Holiest of the holy – unworthily, is a much more grievous sin than

the unworthy reception of the other Sacraments. Besides, it is the blackest ingratitude, as it outrages Our Lord at

the very moment when He comes to us as our greatest benefactor. Hence it is that unworthy communion often hardens the heart

of the sinner. Even temporal punishments, such as sickness and untimely death, are sometimes the punishment of unworthy

communion, as St. Paul testifies in writing to the Corinthians: Therefore are there many infirm and weak among you,

and many sleep

(1 Cor. 11: 30).

2. As regards the body, it is commanded by precept of the Church to observe a fast before Holy Communion. In former times the precept was to abstain from all food and drink from midnight of the preceding night. Although this precept was not in force from the earliest ages of Christianity, yet we have evidence that it dates as far back as the second century. It promotes the reverence due to the Blessed Sacrament, and prevents those abuses of which the Apostle complains (1 Cor. 11: 28). An exception is made in favor of those who, being dangerously ill, receive the Blessed Sacrament as Viaticum; and that so long as the danger continues to exist.

By the Motu proprio of 19 March, 1957, Pope Pius XII decreed: The time for the keeping of the

Eucharistic fast by priests before Mass and by the faithful before Holy Communion, either in the morning hours or in

those after noon, is limited to three hours as to solid food and alcoholic drink, and one hour as to non-alcoholic drink;

the fast is not broken by drinking water... The sick, even though not confined to bed, can take non-alcoholic drink and true

and proper medicines, either liquid or solid, without limitation of time, before celebrating Mass or receiving Holy Communion.

But we earnestly exhort priests and the faithful who are able to do so, to observe the ancient and venerable form of the

eucharistic fast before Mass or Holy Communion... Let all who benefit from these faculties do their best to repay the favor

received, by more shining examples of Christian living, especially by works of penance and charity.

II. In order to prepare ourselves in a way becoming the dignity of the Sacrament, we should, moreover, purify our souls, as far as possible, from venial sins, and awaken in ourselves sentiments – e.g., faith, hope, charity, contrition, desire – which are befitting this solemn moment. For it is the Author of all sanctity that we receive, and the more carefully we prepare ourselves the more abundantly shall we obtain the graces He has in store for us. Our outward deportment, moreover, should express the inward reverence which we bear in our hearts.

Contact us: smr@salvemariaregina.info

Visit also: www.marienfried.com